Search

6346 items

-

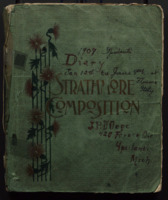

The fifth volume of Jennie Pease D’Ooge’s diary is comparatively short, spanning less than a year, from July 1893 to June 1894. It begins with Jennie and husband Benjamin L. D’Ooge’s two-week visit to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Jennie gives an almost-daily account of the fair’s highlights, disappointments, and novelties, and the accompanying overwhelm and frustration. She rides the Ferris Wheel, sees Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, and witnesses the burning of the Cold Storage Building. She also makes a side trip with a relative to her hometown, Salem, Wisconsin, to visit her aunt Charlotte and old friend Lelia Runkel. Shortly after returning to Michigan, Jennie and Ben, along with their three children, travel north by train to their summer cottage in Charlevoix. Flora Cattermole, their hired girl, joins them to help with household chores and childcare. The summer is spent, with friends from Ypsilanti and elsewhere, fishing, sketching, picnicking, bathing in Lake Michigan, attending church and amateur plays, and boating. The D’Ooges and their friends Bastian and Helen Smits purchase a yacht together, christened the “Helen.” The family stops in Grand Rapids en route to Ypsilanti for a family gathering, or “Kring” in Dutch, with Ben’s mother, siblings, and cousins. The D’Ooges continue to rent 423 Ballard Street in Ypsilanti. Hinting at the Panic of 1893, Jennie remarks on Christmas Day 1893 that she is thankful for what she and her family have “when there are so many thousands starving and cold this winter” and notes that Detroit alone has needed $10,000 per week “to feed the poor who could not get work.” Jennie alludes to a marital issue in March 1894, which appears to have been resolved and left her feeling more grateful for her husband and family. The D’Ooges’ two daughters, Ida and Helen, attend kindergarten and play with classmates and neighborhood friends. Their youngest child, Leonard, is becoming more talkative and making progress with toilet training, but Jennie worries about him for reasons she does not specify. She meticulously tends to her children’s sore throats, earaches, colds, and croupy coughs with homeopathic remedies. When a young girl in her Sunday School class dies, Jennie is critical of her parents for attributing their daughter’s death to God’s will, rather than a lack of care on their part. Galusha Jackson Pease, Jennie’s aging father, is ill and frightened of death, which grieves her. She and Ben try to help her older sister, Ida Pease, sort out his business matters. Ida is their father’s primary caretaker, as well as landlady to several students from the University of Michigan who rent rooms in the Peases’ Ann Arbor home. Jennie has difficulty managing her household accounts on the allowance she is given by Ben. Flora leaves once again and is replaced by a succession of servants: Blanche Scott, Fannie Collier, and Mamie Dickerson. The young women are often unable to handle the laundry, so Jennie hires Mary James or, on one occasion, Wealthy Sherman, a Black woman, to come in and wash clothes. Mrs. Farnam (or Farnum) helps make and make-over clothing, but Jennie still spends many late nights sewing, mending, and darning. The pressures of her family concerns, household stressors, and domestic duties take a toll on Jennie’s mental health in this volume. She describes “the everyday grinding at the home-mill” and writes she “[is] happy as [she] used to be, one day, and the next – [she is] down-cast by a single word or look.” In addition to his position as Professor of Greek and Latin at the Michigan State Normal School, Ben gives public talks, reads a paper before the Philological Society at Ann Arbor, and travels to evaluate a school elsewhere in Michigan for the State Board of Education. Richard Gause Boone becomes president of the Michigan State Normal School, replacing John M. B. Sill.

-

Jennie Pease D’Ooge’s sixth diary spans two and a half years, from June 1894 to December 1896. She, her husband, Benjamin L. D’Ooge, and their children, continue to reside at 423 Ballard Street in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and spend their summers up north in Charlevoix. Jennie’s father, Galusha Jackson Pease, dies on August 15, 1894. Her elder sister, Ida Pease, who had been his primary caregiver, takes the loss hard and plans to build a cottage in Charlevoix. While the D’Ooges are occupied with numerous domestic, social, church, and professional responsibilities, they occasionally break away for fun activities, like a “family nutting-party.” The D’Ooges’ daughters, Ida and Helen, are growing more independent. Ida makes a solo overnight trip to her uncle Martin L. D’Ooge’s house in Ann Arbor, and Helen travels with her aunt Ida Pease by train to visit cousins Ed and Nan Codington in Bartow, Florida. Jennie and Ben’s son Leonard is described as “the best natured boy in the whole world,” although Jennie is frustrated that he continues to wet his pants. On March 26, 1895, the couple welcome their fourth child and second son, Benjamin Stanton D’Ooge, whom they call Stanton. Around the same time as her own baby’s birth, Jennie records the deaths due to childbirth-related complications of two other women with connections to the Michigan State Normal School, Helen Stirling Bowen and Hattie Jenness Coe. While breastfeeding Stanton, Jennie develops cracked skin, followed by a painful abscess and “ague in the breast,” requiring weeks of medical treatment. Jennie is busy with housework and childcare, aided at times by seamstress Mrs. Farnham, washerwoman Mary James, postpartum nurse Amy Jones, and others. Over the course of this volume, the D’Ooges employ several young women in succession as live-in domestic servants, including Mamie Dickerson, Addie Wheaton, Minnie Ellenbush, Minnie Krause, and Carrie Smith. Jennie struggles to balance household duties but is likewise frequently frustrated by the young women she employs, who often fail to meet her standards. After a year of difficulty managing the family’s finances on her allowance, she cedes control over the purse to her husband, “leaving a state of debt & disaster to be settled.” Later, she begins managing the household accounts again, allocated one hundred dollars a month for everything but Ben’s expenses. Ben continues to teach Latin and Greek at the Michigan State Normal School, in spite of the “great rumpus” about Normal president Richard G. Boone’s administration. Some faculty members ask to resign, and Jennie hopes Dr. Boone will resign instead. She is distressed, among other things, by the poor manners and enormous appetites of Boone’s children. Outside of his regular teaching responsibilities, Ben spends much of 1895 completing his edition of Viri Romae, which is published by Guin & Co. in October and proves a success. The following summer he teaches classes and tutors Latin students in person and by correspondence. In addition to promoting his book, Ben is elected vice president of the Charlevoix Summer Home Association, as well as trustee and chorister at Ypsilanti’s First Congregational Church. Jennie notes “great excitement over the N.Y. election,” when Republican Levi P. Morton defeated Tammany Democrat David Hill for the governorship in 1894, “and great victories for the Republicans all over.” She also discusses the “Great Freeze,” back-to-back cold snaps in the winter of 1894–1895, which devastated agriculture in the southern United States (directly impacting her cousin Ed Codington in Bartow, Florida) and disrupted transportation and supply routes nationwide.

-

The seventh volume of Jennie Pease D’Ooge’s diary documents December 1896 through mid-July 1899. It is a period of personal and professional growth for Jennie and her husband, Benjamin L. D’Ooge, as they prepare for a sabbatical in Bonn, Germany. She meticulously keeps track of transactions to and from her personal cash account, as well as social calls to be paid, in the back of her diary. Also in the back of this volume, Ben has written ten sets of questions on Marcus Tullius Cicero’s Third and Fourth Catilinarian Orations. The D’Ooges continue to rent 423 Ballard Street in Ypsilanti and have dinner out of the house. After domestic servant Rose Sauture becomes ill, Minnie Ellenbush Brummel returns to work for the D’Ooges. Mrs. Ruth Vroman and Mrs. Wilson at times do the family’s laundry; Miss Leonard, Miss Hess, and Minnie variously help with mending and sewing; and Mrs. Reinl and Miss Smith are hired as dressmakers. In July 1898 a newspaper obituary announces the death of “Rab D’Ooge, one of the most intelligent and best dogs in the city.” The D’Ooges experience a range of minor illnesses, which Jennie tends to diligently. She suffers from a troublesome ear ailment and goes to the dentist to have a nerve in a tooth killed. Measles sweeps through the family. Ida is only able to attend classes in the morning, as she struggles with headaches, backaches, dizziness, and worries about school. She gets new glasses for her farsightedness, and Helen is instructed to rest her eyes more to avoid glasses for the same condition. Now that the children are older and even the youngest is (eventually) potty-trained, Jennie is able to devote more time to long-neglected pursuits. She enrolls in a Latin class taught by Ben’s assistant, Miss Alice M. Eddy, and takes German conversation lessons. “My brain cells are expanding too rapidly, I’m sure, from so much German and Latin and things, after having been unused for more than twenty years.” Jennie also goes out sketching and, while in Charlevoix for the summer, takes swimming lessons. The nationwide bicycle craze of the late nineteenth century reaches the D’Ooge household. After Ben and Jennie successfully ride a tandem bike, in October 1897 he orders her a Rambler bicycle “at a great bargain” for $50. “I have the same jumping, squealing happiness inside that one of the children would show at such a prospect.” Ben is an avid cyclist and in October 1898 is involved in a legal dispute with the city of Ypsilanti over an ordinance banning cycling on sidewalks. After four years as pastor of Ypsilanti’s First Congregational Church, Rev. Bastian Smits leaves for Charlotte, Michigan. He is replaced by Rev. B. F. Aldrich in May 1897. Ben pledges $150 and Jennie $50 toward a major remodel of the church, anticipated to cost more than $6000. The cornerstone is laid in September 1898. Jennie serves as chairman of the Sappho Club’s nominating committee and sits on the finance and entertainment committees of the local Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) chapter. She is also active with the Young People’s Society for Christian Endeavor (YPSCE) and the Ladies’ Literary Club, and she teaches the Congregational Sunday school infant class. Among the papers she presents at various club meetings are: “Rights of a Child” (“Expect to stir up a hornet’s nest by some of my views,” she comments), “Sanitation in the home – Physiology in the Schools,” and “The Domestic Problem.” Much of the extended D’Ooge family makes an appearance during this volume, as Ben and his siblings travel to visit their aging mother. On February 23, 1899, Johanna Quintus D’Ooge dies at the age of 81 in Grand Rapids. In the following weeks, Ben and his brother Martin L. D’Ooge divide up their parents’ estate among the heirs, Ben taking a house and lot on Spring Street in Grand Rapids as an investment property. There are whispers that Michigan State Normal College president Dr. Richard Gause Boone will be asked to resign, and several have suggested Ben take his place, but Jennie is “so glad he will not think of it.” The D’Ooges hope to move on from Ypsilanti soon. Ben is offered a position at Adelphi College in Brooklyn, New York, but the college is unable to pay him enough. As it is, he must stay behind to teach summer school for the extra money while his family goes up north to Charlevoix. Outside of teaching, Ben is invited, along with Jennie, to serve as chaperone at an Arm of Honor banquet in February 1899, and he is active with the Schoolmaster’s Club. Ben’s textbook Easy Latin for Sight Reading is published by Ginn and Company in 1897. He then works with Harvard professor James B. Greenough to revise Joseph Henry Allen and Greenough’s edition of Caesar’s Gallic War. Jennie assists by researching Gaul and copying references, and the new Caesar is published in May 1898. Other publishers approach Ben to edit more Latin texts, and Jennie writes: “Of course it is all a great honor and some money too – but I wish the work outside his School work did not pile up so fast.” Ginn and Co. agree to pay Ben $1200 a year to study overseas, and in January 1899 the state board of education grants him a one-year leave of absence. Spending time abroad may help him get a position at another school. “But I don’t worry a bit about his chances for promotion,” Jennie asserts. “A man who has done such first-class work always – must win.” In May 1898, following the explosion of the USS Maine and the outbreak of the Spanish–American War, more than 4000 soldiers from Michigan’s National Guard formed four volunteer regiments, which were trained at Camp Eaton at Island Lake, near Brighton. Ben takes seven-year-old Len to see the encampment. They have supper in the mess tent with a friend, Mr. Glaspie (likely recent Normal graduate and football player Andrew Bird Glaspie), who gives Len a badge bearing an eagle and the slogan “Remember the Maine,” which, Jennie says, “is our watch-word in all engagements.” “We are wondering what a week will bring forth in the way of battles. Still we go on quietly living just as if the air were not so full of war and battles down around Cuba.” Jennie loses ten pounds during the family’s last month in Ypsilanti, as she rushes to sell investments for cash, withdraw money from banks, and procure last-minute necessities. At the end of the journal, Ben travels to Cambridge, Massachusetts, while Jennie and the children travel past Niagara Falls (“a bit disappointed”) to Canaan, Connecticut. They plan to meet at the home of Ben’s sister Nellie D’Ooge Utterwick in East Canaan, before journeying on to New York to board their transatlantic ship.

-

In the eighth volume of her diary, spanning July 1899 to the beginning of 1901, Jennie Pease D’Ooge documents her family’s residence in Germany and travels around Europe during her husband Benjamin L. D’Ooge’s sabbatical. She supplements her near-daily entries with photographs taken herself and by friends, dinner menus, concert programs, newspaper clippings, and other ephemera. She also makes sketches and transcribes short samples of music. In the back of this diary, Jennie records observations on German women and children and keeps a list of her young son Stanton’s humorous “speeches.” Enroute to Bonn, Germany, the D’Ooges spend time with Ben’s sister and brother-in-law, Nellie and Henry Utterwick, in East Canaan, Connecticut, and visit New York City. They sail aboard the Holland America Line’s SS Maasdam to Rotterdam, take a steamer up the Rhine River to Cologne, and finally travel by train to Bonn. The family stays first at a Pension [boardinghouse], run by Fräulein Schlingensiepen at Kronprinzenstraße 13. In September, Jennie’s sister Ida Pease joins the family in Bonn, and Jennie and Ben travel to Paris “for a week of fun.” Guided by their “Badaeker,” they dine out, shop, visit landmarks and museums, attend operas and plays, and meet with Ypsilanti friends – including Michigan State Normal College professors August Lodeman and Edwin A. Strong – as well as Ben’s brother and sister-in-law, Martin L. and Mary Worcester D’Ooge. Upon their return, the D’Ooges move into furnished rooms with Frau Witwe Menniger [spelling varies] at Argelanderstraße 61. After moving out of Argelanderstraße 61 to travel in March 1900, Frau Menniger brings a suit against the D’Ooges, claiming they owe her 50 Marks. Later, in May 1900, the D’Ooges move to Luisenstraße 38 in the Poppelsdorf area of Bonn, run by Frau Taxer [or Taxar] and Fräulein Cornetius. The D’Ooges develop an active social life in Bonn, socializing with their fellow boarders, scholars, and upper-class Germans and Americans. In particular, they befriend American Congregational pastor Nathaniel Rubinkam, his wife Sarah Shoemaker Rubinkam, and their children. They learn about local customs and celebrate holidays with their neighbors, attend elegant dinner parties and more raucous gatherings (“What would our temperance friends in America say to such goings-on!”), and enjoy excursions to nearby sights. Jennie describes this as a happy period for her family: “Such glorious days are what we shall long remember, after we are back, to the Grind of America.” Jennie spends much of her time mending and altering clothing, washing dishes, cleaning the apartment, and tending to lamps, but she attempts “to do less working and more studying. Have decided that I am not here to do washings.” She seeks out opportunities to practice German, although she is frustrated with her slow progress, and enjoys conversing with the “gebildete Damen” [well-educated, erudite ladies] at Luisenstraße 38. She also stays in written communication with friends and family in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and elsewhere. Ben studies at the University of Bonn and “is deep in his Cicero,” working on another book for his publisher, Ginn and Company. Because the family “can get along so economically” in Germany, they decide to stay in Germany for a second year, enabling Ben to continue his studies. The elder D’Ooge children attend school in the mornings, Ida and Helen a private girls’ school and Len a Gymnasium [German academic high school]. They learn German quickly and make friends with classmates and neighbors. Ida and Helen sing in a school chorus and practice duets together, and in her free time “Ida has taken violently to knitting.” Jennie teaches Stanton at home, supposing “he must learn to use his head a little before next year” when he starts school. The children experience various health ailments. Ida has eye problems from reading too much German text, suffers from neuralgia, has “not much vitality,” and one lung “might be a trifle affected.” Helen has eczema on her hands and, later, is instructed to eat more fruit and less meat and to get lots of exercise. Len has a bilious attack and jaundice, and subsequently Ida and Helen both have jaundice, too. As usual, Jennie seeks the help of local doctors while also treating the children with homeopathic remedies. In October 1899, Jennie and Ben take a two-week trip to the Netherlands. In addition to major cities and popular destinations, they visit Zonnemaire, the Dutch village where Ben’s older siblings were born. They take photographs of Ben in front of his grandfather’s house and his father’s cottage. “I look back with great satisfaction upon our Holland trip. Certainly two people never before had such a two weeks of fun. We have enjoyed every minute, and gained a fairly good idea of the quaint little watery country. I have even more respect for the Hollanders than before, when I see the infinite pains and trouble they have been to, in order to keep their homes after they had made the land. God made the earth – but the people made Holland.” In early March 1900 Ben embarks on a three-month journey to Italy and Greece, where he again meets with Mart and Mary D’Ooge, as well as Ann Arbor High School teacher Prof. Judson G. Pattengill and his daughter Caroline “Carrie” Pattengill. Ben documented his travels in his own journal. Later in March, Jennie, her sister Ida, and the children travel via Frankfurt and Nuremberg to Munich for about six weeks. They spend time with Prof. Lodeman’s wife, Frances, and daughter, Hilda. Mrs. Lodeman is described as a “poor, nervous invalid” who is temperamental and at times even suicidal. Although her sightseeing is sometimes hampered “on account of so many children,” Jennie attends numerous operas and spends hours in art museums, including an exhibition of Secessionist art. At the children’s urging, the family watches the wedding procession of Princess Mathilde of Bavaria and Prince Ludwig of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. They take a four-day excursion to Murnau, Oberammergau, Bavarian King Ludwig II’s Linderhof Palace, and Lake Starnberg, before returning to Bonn via Augsburg and Heidelberg. There are some missed trains, forgotten luggage, and other stressful incidents on the trip, but according to Jennie, “All it takes is some nerve to get along.” Jennie, Ben, and their daughters spend four weeks in the Swiss Alps in September 1900, traveling via Mainz, Strasbourg, and Bern to Lucerne. Ben and Ida climb over 3000 feet up Mount Pilatus, and Ida is reportedly “the first little girl to go up.” The family explores “Tell country,” reading excerpts of Friedrich von Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell while trekking through the mountains and visiting landmarks associated with the Swiss folk hero. They travel back to Bonn by way of Frankfurt, where they visit the Johann Wolfgang von Goethe house museum. In late October 1900, Aunt Ida Pease embarks on a solo trip to Berlin and Dresden. Meanwhile Jennie takes Stanton to Belgium for a week. They visit Aachen and Antwerp enroute to Ghent, where they have been tasked with buying rabbits from a Flemish breeder and having them shipped to Jennie’s cousin Ed Codington in Florida. They spend two nights in Brussels on the way back, and they go to the iconic Manneken Pis fountain: “I did not let Stanton see [the fountain] very plainly – it is too vulgar. To me it is characteristic of Brussels. I believe there is as much low-lived vice as in Paris.”

-

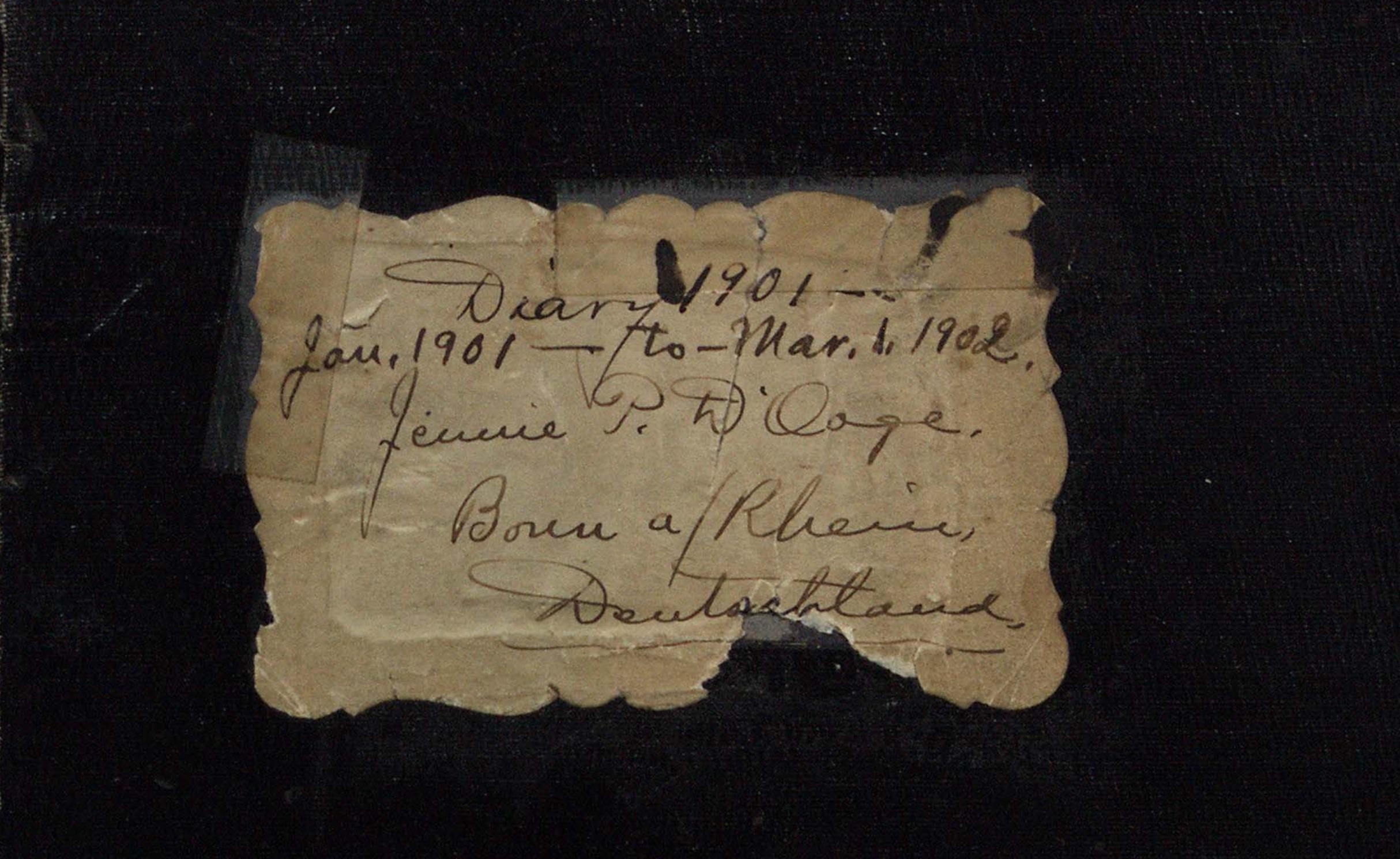

The diary of Jennie Pease D’Ooge dated from January 1901 to March 1902 chronicles the final months of her family’s two-year stay in Germany and their return to the United States. Her husband, Benjamin L. D’Ooge, on sabbatical from his teaching position at the Michigan State Normal College, completes his doctoral Arbeit (dissertation) and oral exam and earns a Ph.D. from the University of Bonn. Their four children – Ida, Helen, Len, and Stanton – attend school and befriend local children. The family, accompanied by Jennie’s older sister, Ida Pease, continues to rent rooms from Frau Taxer and Fräulein Cornetius at Luisenstrasse 38 in Poppelsdorf, a district of Bonn. The suit filed against the D’Ooges by their former landlords, the Meningens (or Menningens, Menningers), is settled in February 1901. This volume is peppered with German words and phrases, as Jennie practices the language and describes local customs. Sewing and mending still demand a lot of her time, but she finds great pleasure in learning Schnitzen, or woodcarving, writing: “I am so interested in my Schnitzing that I can hardly stop long enough to attend to my family’s most pressing needs. It is the most fun I have had in many a day.” She also helps Ben correct his proof of Cicero: Select Orations for Ginn and Company, as well as his dissertation. In April 1901, while Ben travels to Milan, Florence, and Rome, Jennie takes a 17-day solo trip by train to Berlin and Dresden, returning via Meissen and Leipzig. This is the longest she has been away from her husband and children, and she writes: “Such a luxury not to think of anything about work or anything but selfish pleasure. I wish that every mother could ‘run away from school’ this way, once in a while.” She visits numerous landmarks, enjoys long hours in art museums, attends several opera performances, and proudly economizes wherever possible. In Berlin, Jennie also spends time with Maude Jerome Sherzer, wife of MSNC geology professor William H. Sherzer. “She [Mrs. Sherzer] has had a hard time over here; and seems to be almost bitter against all married life in general. Thinks it is a ‘slave’s life’ and so it often is. But would we be as happy under any other conditions? I say No, a thousand times No.” In June 1901, the D’Ooges leave Bonn, traveling by steamer down the Rhine River to Rotterdam, where they board the Holland America Line’s SS Statendam bound for New York. Once they recover from their seasickness, the travelers enjoy playing cards and shuffleboard, spotting whales and porpoises, reading, and resting. Jennie and Ben celebrate their sixteenth wedding anniversary at sea. The D’Ooges reach New York City in the midst of a heat wave, so, after just a brief visit, they take the train to Detroit and then on to Ypsilanti. Jennie records the assassination of President William McKinley in September 1901. “In every city the day [of his funeral] was observed by stoppage of work & special memorial church services.” Otherwise, the normal rhythms of life resume: summer in Charlevoix full of sailing, swimming, dancing, German lessons, and socializing; setting up a new rented home in Ypsilanti, canning pineapple sent from cousins in Florida, and playing golf in the fall; and clubs, entertaining, church fundraisers, doctoring illnesses, and “the grind of house-work & mending” in the winter. Jennie joins the Whist Club, is elected president of the Ladies’ Aid Society of Ypsilanti’s First Congregational Church, and participates in the Sketching Club at MSNC art instructor Hilda Lodeman’s studio. Ida and Helen formally join the Congregational Church in January 1902. “What a busy, rushing life!” Jennie writes, “The girls have no time to do anything.” The D’Ooges again employ young women as live-in domestic servants, including Harriet Biery, Bertha Thompson, Mabel Love, and Jennie de Boer. Ben returns to summer school and his regular teaching duties, finishes his Cicero proof, gives lectures on topics such as Athens, Rome, and Pompeii, and travels on business to New York, New Haven, and Boston. He hopes for a position at Yale or Teachers College, Columbia University. Jennie agrees with a friend who says: “We have our heads up looking for a bigger town.”

-

Jennie Pease D’Ooge’s tenth diary spans from March 1902 to June 1903. She, her husband, Benjamin L. D’Ooge, and their four children continue to live at 602 Congress Street in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and spend summers up north in Charlevoix. In May 1902, Jennie accompanies Ben when he travels to give a lecture in Chicago. She writes: “I hesitated at first on account of the cost – but as I told Ben, it will be all the same in a hundred years, and we shouldn’t deny ourselves everything.” During their trip, Jennie meets with cousin and old friends, lunches at Marshall Field’s, attends musical and theatrical performances, and visits two major Progressive educational institutions: Jane Addams’s Hull House and John Dewey’s Laboratory Schools. Jennie has a full calendar of social, religious, and charitable activities, and she laments being so busy (“I am in too deep – cannot see daylight”). She serves as president of the Ladies’ Aid Society at Ypsilanti’s First Congregational Church. In April 1903 she joins Abbie Hunter Pease, wife of Michigan State Normal College music professor Frederic H. Pease, as a “patroness” to the Harmonious Mystics, a sorority established in 1900. Jennie is also recruited into the local Whist Club. In her spare time she practices pyrography, burning decorative designs into wooden objects, including her new ping-pong paddles, and begins teaching classes on the art. She reads widely. Among other books, she comments on The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900 by Thomas Dixon and quotes extensively from Confessions of a Wife by Mary Adams, both published in 1902. Ben is also active both professionally and personally. In addition to teaching classics at Michigan State Normal College, he gives lectures on Greek and Roman topics and works to revise Allen and Greenough’s New Latin Grammar. According to Jennie, “Ben has some glimmer of hope of a change – to Oberlin or Stanford University or somewhere away from Ypsi!” He becomes a second degree Mason. The Normal College has a new president in fall 1902, Lewis Henry Jones. Privately, Jennie thinks he looks “queer” and “dissipated” after first meeting him. Two MSNC colleagues and good friends die suddenly: August Lodeman, professor of modern languages, and Austin George, former director of the college’s Training School and later superintendent of Ypsilanti Public Schools. Jennie notes “a growing re-action against co-education in Universities,” as some, herself included, do not believe it is producing the “best results.” The children are becoming more mature and independent, although Jennie at times worries about how they “seem to utterly lack any idea of care for themselves,” as well as how much food they consume. All have active social lives, spend weekends in Ann Arbor with their Aunt Ida Pease, and take part in music recitals and theatrical performances. They suffer from various ailments, which Jennie diligently treats with homeopathic remedies and visits to the doctor. Mumps sweeps through the family in April and May 1902. In March 1903, an outbreak of smallpox sends a neighbor girl “to the pest-house in Detroit” and pushes Jennie to have her children vaccinated. Ida is initiated into the Beta Nu Society, wants to dance with partners at the Charlevoix hop, suffers from acne, and receives sixteen lumps of sugar from a friend when she turns “sweet sixteen.” Helen, nicknamed “Arlie,” finishes grammar school and “graduates into the troubles of High School.” Both girls “have reached the shirt-waist age.” Len struggles to pay attention in class, but he helps out with chores, leads a Junior Christian Endeavor meeting, and enjoys playing with friends and his toy steam engine. Stanton is good natured and earnest. For his seventh birthday, his Aunt Ida gives him a pair of guinea pigs, which quickly multiply. A neighbor gives the boys a puppy, Skele, “the dearest, softest, naughtiest little rascal,” but he dies from distemper before his first birthday, “a sore trial” to the whole family. Shortly thereafter, Stanton brings home a large gray and white cat. For much of this period, the D’Ooges take their dinners out and, until June 1903, pay Mabel Love to help with cooking and washing. The family has difficulty obtaining coal to heat their house in the winter due to the anthracite coal strike of 1902, and Jennie worries that “[t]here will be immense suffering in the poor classes.” There is much confusion in Ypsilanti as the town attempts to switch to Standard Time in early 1903. In this volume, Jennie celebrates her “—rd” and “forty __th” birthdays, remarking, “Time flies, these years.” In the very last entry of the diary, she writes: “Our eighteenth wedding-anniversary. We ought to celebrate, but doubt if we have time to even remind Ben.”

-

Jennie Pease D’Ooge’s eleventh journal begins in late June 1903, as her family departs for their summer cottage in Charlevoix, and follows their daily lives through the beginning of May 1904. In Charlevoix the D’Ooges visit with family and friends, play games (such as flinch, pedro, charades, euchre, and whist), and sail the Amy. Jennie’s husband, Michigan State Normal College classics professor Benjamin L. D’Ooge, continues to serve as a trustee of the Charlevoix Summer Home Association. Their daughters Ida and Helen get up to “great antics” with other teens and are eager to attend hops at the resort hotel. Their elder son Len also enjoys hops, as well as fishing, and their younger son Stanton stays closer to home, playing with other children, reading, and spending time with his parents. The family plans to remodel their cottage at the end of the season. Jennie’s sister, Ida Pease, rents out her Ann Arbor house for part of the summer and stays in her own cottage in Charlevoix. In Ypsilanti, the D’Ooges continue to rent 602 Congress Street. Edith Hoyle, a Normal College student, lives with them and assists with housework. The family regularly takes dinners at a boarding house, cafe, or hotel, rather than cooking at home, or they purchase dishes from the Women’s Exchange to round out a home-cooked “luncheon.” Jennie bemoans how much food her four growing children consume: “It seems as if the capacity of my family for good things to eat is absolutely unlimited. I have to buy just twice as much of everything as I used to.” She has a new gas range, which she says is “fine,” although she worries that the gas will cost too much and complains that the water heater ran up the November gas bill to $6.20. Ida and Helen are given more responsibilities at home, including meal planning, baking, and sewing, to varying degrees of success. “The girls try to help but their interest is apt to wane when they have company or a book to read. I suppose it is because they know I am here, and weak-minded enough to spring to the front whenever they hold back.” Jennie laments that she is “getting so inexcusably, inconceivably homely” and says, “I tell the children if I only did not have to push so much and do all their thinking for them I wouldn't get so tired.” A humorous example of this occurs in March 1904, when Ida and Helen travel by train to stay with Jennie’s longtime friend Kittie Castle Hattstaedt in Chicago. Soon after their departure the girls send a telegram home saying that they cannot find the trunk key, and Jennie promptly telegraphs back: “Trunk key in Ida’s pocket. What next?” Mrs. Crosby and other women are often hired to do the laborious chores of washing and ironing. Jennie spends much of her time sewing, either by hand or with her new lockstitch machine, but when she needs to produce a lot of clothing in a hurry, she pays Agnes Fike (or Fyke) $5 a week plus lodging for two weeks to help her sew about twenty garments. She also has an underskirt made for herself and a new spring suit made for Helen at Ypsilanti’s W.H. Sweet & Son, arguing that the quality and durability compared with ready-made clothes justify the expense. Jennie continues to serve as co-patroness of the Harmonious Mystics, a Michigan State Normal College sorority, with fellow faculty wife Abbie Hunter Pease. They are pleased to pledge MSNC president Lewis Henry Jones’s daughter Edith, to the chagrin of librarian Genevieve Walton, who had spent more than a year rushing Edith for the Zeta Phis. Mrs. Pease’s moods can change quickly, she acts “real cat-y” to Jennie during a sorority event, and Jennie describes her as “so cold and indifferent and bored,” highlighting some tension between the two. Jennie is also a chaperone of the Halcyon Club, alongside Eva Green Hoyt. Jennie is elected president of the Women’s Union of Ypsilanti’s Congregational Church, and she remains active with the Congregational Ladies’ Aid Society. She is also elected Corresponding Secretary of the Ladies’ Literary Club and serves as chairman of the press committee. She attends thimble parties, church fundraiser socials, and “swell” luncheons. When she has time, she enjoys decorative woodcarving and burning, and she reads several books, including contemporary novels and historical fiction. Jennie maintains contact with numerous friends from different stages of her life, including the D’Ooges’ two years in Germany. In December 1903, she attends the funeral of family friend Sarah Swope Caswell Angell, wife of University of Michigan president James B. Angell. In addition to teaching at the Normal College, Ben presents at the National Education Association conference in Boston in July 1903. He also speaks to local groups, including giving a talk about Holland in Wayne, Michigan, where “he had a most appreciative audience of Podunkers from Podunk.” As club president, he organizes a meeting of the Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club and the Classical Conference in Ypsilanti in March 1904. He is also elected president of the newly-created Ypsilanti Choral Society, a town-and-gown chorus directed by Prof. Frederic Pease. He enjoys playing golf in good weather. Ben and Jennie take the train into Detroit several times on various errands, including meetings about their investment in the Black Diamond Mine (which Jennie regrets), sailing on the Detroit River with friends Louis C. and Jane Mahon Stanley, and attending a performance of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice starring Henry Irving as Shylock. Especially during the winter, there seems to be an endless rotation of illnesses in the D’Ooge family: toothache, earache, headache, sore throat, “malarial symptoms,” lingering coughs, “Cuban itch,” fears of diphtheria. Nevertheless, the children are busy with concerts, sporting events, and social gatherings. Ida is appointed to participate in an oratorical contest and the Junior Exhibition. Helen attends Junior Endeavor at the Congregational Church and is described as a “dear, faithful little Christian.” Len sings with the Episcopal Church boys’ choir and plays football. Stanton struggles with arithmetic. In February 1904, the boys go, perhaps for the first time, “to see some Moving Pictures at the opera-house.” During a visit to her sister Ida’s house in Ann Arbor, Jennie looks through family papers: “[I] read the diaries of Grandma Deuel, Father & Mother, written about the time they were married, and on through the next eight years, until mother’s death. It seems strange to think she was only 28 yrs. old when she died. (She was born in 1832.)” At least some of these documents are today in the Eastern Michigan University Archives.

-

Diary of J.P. D'Ooge from 1904 May to 1906 May

-

Diary of J.P. D'Ooge from 1906 May to 1907 November

-

Diary of J.P. D'Ooge from 1907 November to 1907 December

-

Diary of J.P. D'Ooge from 1909 January to 1909 June

-

Diary of J.P. D'Ooge from 1909 June to 1910 August