Veterans History Project

Item set

- Title

- Veterans History Project

- Description

- This collection contains oral histories with Ypsilanti and Washtenaw County veterans collected by the Ypsilanti District Library, Ypsilanti Rotary, and the Eastern Michigan University Archives for the Veterans History Project. The VHP is part of the Library of Congress American Folklife Center which aims to document, preserve, and make accessible the stories of veterans from World War I on. Interviews with local veterans are housed at the Eastern Michigan University Archives in addition to the LOC. Oral histories continue to be processed by the American Folklife Center and the collection is updated regularly.

- Creator

- Ypsilanti District Library, Ypsilanti Rotary, Eastern Michigan University Archives

- Publisher

- Eastern Michigan University Archives, Ypsilanti District Library, and the Library of Congress American Folklife Center

- Is Part Of

- 018.VHP

- Rights

-

The Veterans History Project Collection includes oral histories along with documentary materials such as original letters, diaries, photographs, and memoirs. Veterans and interviewers contribute these materials to the Library for scholarly and educational purposes, retaining any copyright they may hold. Therefore, permission must be obtained before using the interview or other materials in exhibition or publication. Researchers or others who would like to make further use of these materials should contact the Veterans History Project for assistance.

As a publicly supported institution, the Library generally does not own rights to material in its collections. Therefore, it does not charge permission fees for use of such material and cannot give or deny permission to publish or otherwise distribute material in its collections. Responsibility for making an independent legal assessment of an item from the Library’s collections and for securing any necessary permissions rests with persons desiring to use the item. - Contact VHP and The American Folklife Center

Items

6 item sets

-

-

-

In the Fall of 2022, Matt Jones’s Oral History Techniques class conducted a set of interviews documenting the stories behind the student unrest on Eastern Michigan University’s campus from 1966-1972. Caught up in the Civil Rights Movement, anti-war protests, women’s liberation, fights for student rights, and a hometown serial killer, EMU found its place within the greater cultural shifts taking place on college campuses across the country. The narrators taking part in this project range from student activists, to administrators, to police officers, each providing a unique perspective in this story. Five Days in May reflects a period of time in EMU’s history where the campus made sure its voices were heard.

-

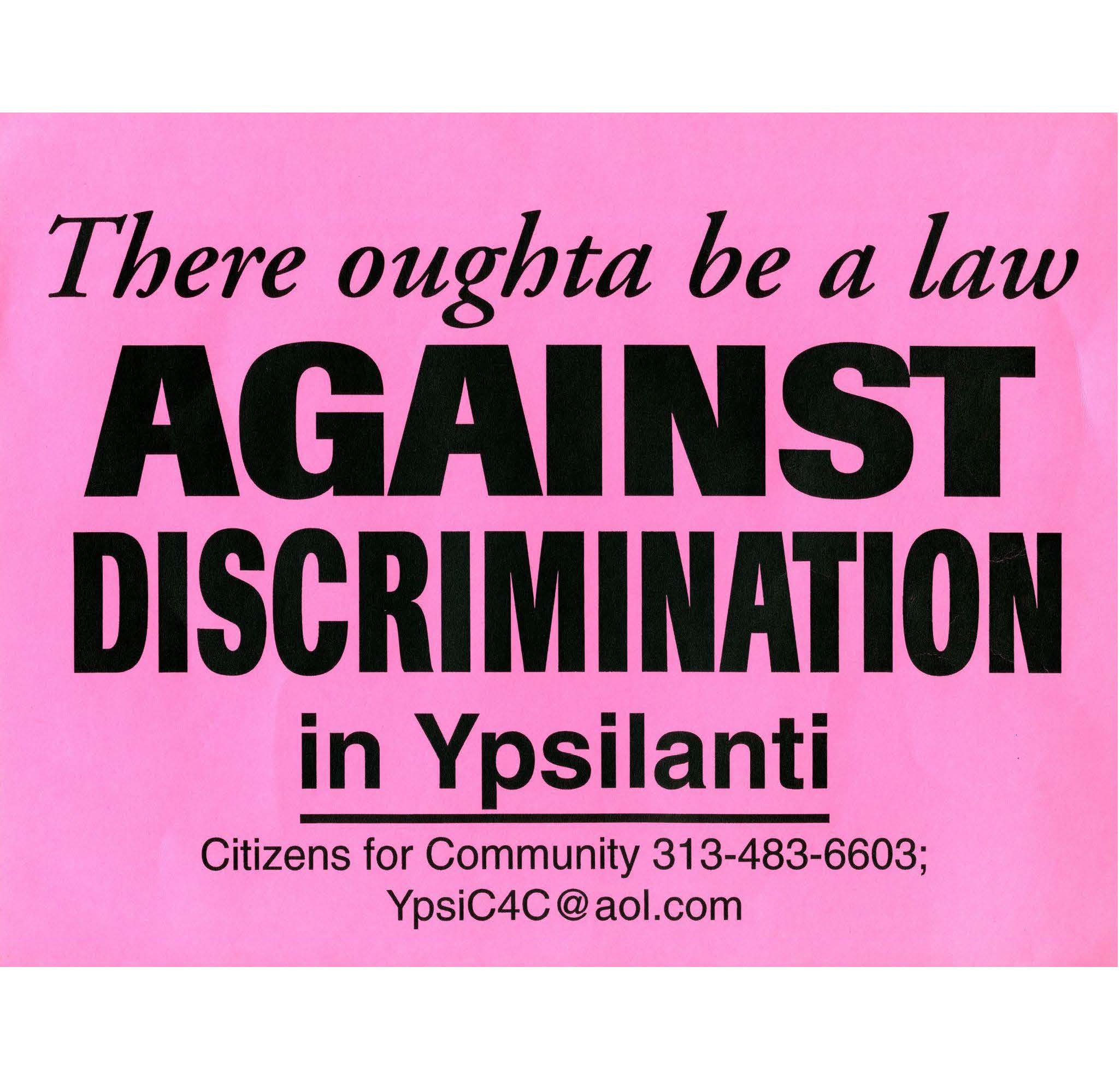

In 2021, Eastern Michigan University Archives lecturer Matt Jones began documenting the story of Ypsilanti’s Human Rights Ordinance #1279 in an effort to explore the ways in which local queer activism has evolved multi-generationally in Ypsilanti. What began as a refusal of service by a local print shop to a small EMU student group quickly turned into a years-long battle over who was deserving of basic human rights. To the LGBTQ activists and community members documented here, they had always been present in the community: working, paying taxes, painting their houses, mowing their lawns, attending council meetings, and even serving on council. This ordinance battle was about more than just LGBT rights—it was about protecting the human rights of all Ypsilantians.

-

This collection contains oral histories with Ypsilanti and Washtenaw County veterans collected by the Ypsilanti District Library, Ypsilanti Rotary, and the Eastern Michigan University Archives for the Veterans History Project. The VHP is part of the Library of Congress American Folklife Center which aims to document, preserve, and make accessible the stories of veterans from World War I on. Interviews with local veterans are housed at the Eastern Michigan University Archives in addition to the LOC. Oral histories continue to be processed by the American Folklife Center and the collection is updated regularly.

-

This oral history project explores EMU's partnership with Jewish Family Services of Washtenaw County in providing on-campus housing for twelve Afghan families who fled their homes when the Taliban took over in 2021. The families stayed in the Westview Apartments from January to June of 2022.

113 items

-

(Newspaper Article from January 3, 1945): Roy Irving Albert, 20, only son of Mr. and Mrs. Roy Albert, 312 Saginaw, has been missing in action in Germany since December 12, his parents were told in a telegram from the War Department received yesterday noon. Overseas since September, he served as a gunner in an Infantry Division believed to be attached to the Third Army. His parents know that he participated in at least three battles prior to the one in which he was reported missing. In his last letter, dated Dec. 3, he wrote that he was living in a cellar in France, waiting to be sent out again. A graduate of Norway High, Albert was a pre-med student at the University of Michigan when he was inducted March 15, 1943. He received his basic training as a rifleman in the Infantry at Camp Roberts, California, following which, as the result of an aptitude test, he was selected to attend the University of New York as an engineering student in the ASTP program. During his training period in the states, Albert tried to get into the Air Corps. With this in mind, he dropped his studies as an ASTP student. After serving in various camps, he was notified last summer that his transfer into the Air Corps was approved. A month after he arrived at the Balden Air Base in Mississippi for his Air Corps training, the Aviation Cadets were discontinued, and he was sent back to the Infantry. He was last home on furlough in June. Albert's parents were notified in a letter written May 9, 1945 that he had been liberated and was safe in Germany.

-

John Anderson was born in the small town of Catch All, Tenn. on May 26, 1923. John was always interested in airplanes. After graduating from high school, he joined the Navy on August 11, 1941 because he could see that war was coming. John was trained as a machinist in Norfolk, Great Lakes, and River Rouge, where he met his wife. Enlistments lasted for six years at that time. He was shipped to Guam and later to Guadalcanal, where he serviced fighters that were stationed there. Since the island was not completely secured, servicemen were continually finding and killing Japanese soldiers. John said that he and others were continually bombed by Japanese airplanes, mostly at night. John did not receive any wounds, but he did have malaria three times. John was discharged in 1947, and returned to Tennessee. He took a job as a watch repairman, and eventually had his own business. John would repair watches for jewelers in the area Until he retired in 1988. John was very proud of the fact that he built his house, a three-bedroom one, in Tennessee. When he fell down the stairs last year, his family got him to move to Michigan, where his four children live. They were concerned because his Tennessee home was nearly half hour from the hospital. Here in Michigan, John has been and continues to be treated by the Veterans Administration Hospital. He and his wife live in American House senior living, in Ypsilanti. John was especially proud of his Tennessee ancestors who, during the Civil War, helped a severely injured soldier from the North. When other Northern soldiers were in the area looking for food, this recovering soldier told them not to bother this family, since they had saved his life.

-

Russell trained at Fort Knox, Fort Polk, and Fort Benning before being sent to Vietnam. He was a squad leader and went out on numerous patrols. For most of his tour of duty, his squad was fighting the VC, except for one soldier in a Chinese uniform that they killed, which was unsettling. Russell was wounded after only three months in Vietnam. He was shot in the stomach but fortunately his belt buckle took most of the impact. Russell was operated on, losing a kidney as well as other internal organs. He was awarded for Valor; having gone out into a situation that he was not required to go on. Russell has an 80% pay for disability from the Army. When he returned, he got married and had five children. He returned to work at GM. One incident that he mentioned happened when a supervisor had a heart attack and died near him. This triggered PTSD because it brought him back to his Vietnam experiences. Nevertheless, Russell has a very positive attitude about his Army experiences.

-

As students at Notre Dame, John and his roommate enlisted in the Naval Reserves. He was called up when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and was allowed to finish his studies in an accelerated program. He first applied for submarine duty but “flunked that.” Afterwards, he trained in underwater demolition. He was shipped to the South Pacific where he spent 30 months. He became a Beach Master, with a responsibility to go in with the landing Marines. While on the beach, he would direct the supply ships, and would send the wounded and dead out to the hospital ship. He recalled one incident in which someone tried to countermand his order to bring men out to the waiting ship. He had to pull a gun to make sure that his LSV1 would bring the wounded out to the ship. Several years ago, he ran into one of the marines who was transported to that ship. The now-civilian told John he saved this man’s life. John saw duty on Saipan, Guam, New Guinea, Iwo Jima and several other islands. He was impressed with the number of graves on Iwo Jima – 2,605. John was eventually sent to Hawaii for a rest. While there, he was told to go to Manila to prepare for the invasion of Japan. John feels that dropping the Atomic Bomb saved his life, and those of many other GIs. After the war, John went to the University of Detroit Law School, but never practiced. He got married, had five children and went into the hotel business. Now, he is in Economic Development, trying to “sell” Farmington Hills.

-

Ernest Aroffo attempted to enlist in 1942, but he didn’t weigh enough, and was turned away. He was drafted six months later in 1942. Ernest was sent to Fort Custer for training in October 1942 and stayed there for two years at the request of his superiors. In 1944, he was sent to Fort Sheridan for more training, and then to the field hospital group at Camp Grant in Illinois. His last stop in the US was in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he was promoted to 1st Sergeant of the 1st platoon. As 1st Sergeant of the 1st platoon, he had control of duties in the ranks. He and his others arrived at the Normandy beaches in October 1944 after D-day. Ernest later described his experience arriving on the beach after the battle. His mobile hospital unit was 29 men, with two nurses and two doctors. Their job was to work with the 3rd Army and keep up with them, and to perform medical services, mainly surgery. Ernest’s unit traveled with two jeeps, a two & one-half ton truck and an ambulance, while the 3rd Army was mostly a mechanized division. From France, they traveled through Belgium and Luxembourg, staying for about three days each. Eventually, his unit and the 3rd Army would enter Germany and visit cities like Metz and Nuremberg. The mobile unit mainly worked within cities, using ambulances to transport those in need of treatment (from the field and those within the cities). They were within 15 minutes of conflict, so they had access to the wounded. His unit later entered a concentration camp and was assigned to delouse the detainees. He described to listeners what he saw, including the barracks and the victims. Ernest’s last stop was Nuremberg. and he later described to listeners the two hospital buildings he worked in, and the patients he saw. While in Germany with the 3rd Army, he volunteered to rescue an injured man in a snow-covered minefield. He successfully brought this man back to the medical unit. Ernest was twice given a bronze star for his heroism. The first was from General Patton, who at the time was not a full 4-star General, and thus without the proper authority to award the star. So, a second General, who was a 4-star, awarded Ernest a second bronze star later. He kept a memorandum while overseas documenting the experiences he had. His old platoon now meets as a veteran’s group.

-

John Bahadurian was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1925. In high school, John took a class on Morse code. By the time that he turned 18, most of his friends were in the Air Service. When John enlisted upon graduation, he was sent to Calcutta, India. Because of a myth circulated amongst the other soldiers about Calcutta - if you stayed in India for too long, you would not be able to have children - John asked to be reassigned. He was sent to China with the Flying Tigers, a group of the American pilots attached to the Chinese Air Force. There, John was transferred to and did cryptographic work for the XX Bomber Command including, work as a finder that guided lost planes back to base with radar, and as a decoder of messages from Washington. About once a week, his base was bombed by the Japanese from Nanking. John recalls meeting Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang’s wife in Shangdu. John was sent from there to Shanghai, where he awaited the boat home. John was 21 when he left China.

-

Thomas Barton was born in Winnipeg, Canada on November 14, 1919. He enlisted in the Army from Detroit, Michigan shortly after Pearl Harbor. He had his basic training at Camp Haan in California. Afterwards, Thomas was sent to San Francisco, and eventually was assigned to the 78th Coast Artillery. Thomas was first sent to New Zealand, and later took part in the invasion of Bataan and Corregidor, for which his unit won a Presidential Citation. During and after his service, Thomas had malaria 13 different times. After his discharge he settled in Southgate, Michigan.

-

Edna Bauman supported the war effort by working as a civilian employee in the Willow Run Bomber plant, in Ypsilanti, Michigan. She had graduated from high school and wanted to make more money than the average office worker, so she applied for jobs in industry. Edna was hired at the Willow Run plant in May 1943, when she was 23 years old, and worked on B-24 planes until August 1945. She was originally hired as a riveter, but the station of the plant where she worked did not have the type of riveting that she knew how to do, so her supervisor put her to work sound-proofing the airplanes. Because she was trained as a riveter, her supervisor offered her the higher male riveter wage to keep her on the line as a sound-proofer. Edna was the only female worker at her station, and she remembers many comic moments and always being treated fairly. During the war, many famous people visited the Willow Run plant, and Edna was present when Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt toured the facilities. Edna was one of the last workers to be laid off after the war ended, because of her specialized sound-proofing training, in August 1945. Edna, who had been married for four months by the time she left Willow Run, remained jobless for a year and a half. She then applied for a job in Plymouth and was hired to stuff cushions on an assembly line, taking time off to have a child, but remaining employed until her retirement.

-

Roy Birmingham, Jr. was born in Dayton, Ohio on December 21, 1928. He was nearly 22 years of age when he was drafted in 1950. After basic training and specialized training, Roy was assigned to the 8th Army Headquarters (EUSAK) Signal Corp. He spent time in Taegu and Yeondeungpo, Korea. Roy obtained the rank of Sergeant First Class before he was discharged in 1952. Roy currently lives in the Fox Run Living Center, in Novi, Michigan.

-

Nathaniel Blair was born in Detroit on April 15, 1915. He has a degree in Forestry from Michigan State University. Before the war, Nathaniel was a parts inspector at a machine shop and had two children. He was commissioned in the U.S. Navy on March 28, 1944. After basic training in New York, Nathaniel signed up for P.T. Boat training. Three months of training in the Atlantic involved notable exercises with destroyers. Afterwards, he reported to San Francisco, assigned to Round 24, and shipped out to the Philippines. They pulled into Leyte Gulf near Samar. His P.T. Boat was heavily armed with guns on the deck, and never once fired a torpedo or sank a Japanese vessel. Most patrols were done at night. During the invasion of Zamboanga, his ship patrolled around the invasion area, but never fired upon the enemy. After the P.T. base at Caldera Point was destroyed, a converted tender aided them for about four days until another Navy tender could arrive. Nathaniel remembers a trip past the island of Bongo. Despite being at least a mile out, their boat came under fire. A man in the turret was hit in the neck by shrapnel, the only casualty his boat ever took. The boat was damaged and had to be towed back to the tender. Two other boats in their squadron had been lost. One was destroyed in a radar check. These involved passing the shore while idle, or quiet. If the enemy shot at you, then they had radar. This ship took so much fire during a check that it was split in half. The boat took at least four casualties, including a man who had only been in the Philippines for a month. Nathaniel's squadron destroyed enemy objects such as oil tanks and docks. He remembers a lot of trouble around Jolo. The Moros tribe supplied information to the Americans. Nathaniel received a ribbon with a star for serving in the Philippines, a ribbon for serving in the Pacific, and a ribbon for the victory. He received $165 a month, $150 of which he sent straight home. Nathaniel went into inactive reserve on April 8, 1946. He worked for the City of Detroit's Parks and Recreation service until retiring in 1973.

-

Frank Bostic was born in Detroit, Michigan. His family moved to Ann Arbor when he was very young, and he attended the city’s high school. Frank played football and ran track (he was the first Black athlete to be voted captain). While going to school, Frank worked as a paper boy. He said he earned more than his father, who was employed by WPA. After high school he was drafted. He relates many instances of prejudice, including being assigned to sleeping in tents. He was told it was to prepare him for battle conditions; however, it was only the Black soldiers who slept in tents. Frank was eventually assigned to the 92nd Infantry, an all-Black unit. He fought in Italy and was seriously wounded. In spite of his wounds, Frank is credited with saving three other soldiers, for which he earned his Bronze Star. He spent nearly a year in hospitals before being discharged. When Frank returned from service, he tried to join the VFW. They refused him membership because he was Black. He eventually joined a different VFW. Frank married after the service and had six children: three boys and three girls. During his married life, he worked as many as three jobs to make sure his children received an education. His wife died just short of their 50th anniversary.

-

Maggie Brandt was a surgery resident in New Mexico in 1992, when she was recruited into the Army reserves. She wanted an opportunity to give back to her country. Therefore, Maggie went to officer basic training in San Antonio and was assigned as a reservist to Brook Military Hospital’s burn unit. As an army reservist, she was assigned to the 452nd combat support hospital, out of Fort McCoy. Her first deployment was to Afghanistan in 2003, where she was stationed at the air base in Bagram. While in Afghanistan, she saw little active combat. She worked with small mobile medical components, of about 30 beds. She took care of local nationals (Afghan citizens) and Americans in Afghanistan. The most common injuries were from mines. Most Americans were evacuated to Germany within 72 hours because of the better specialist care and proximity to home. The most severe and common injuries were mine-related, but Maggie also saw sniper injuries and vehicle crash injuries. She thought the Afghanistan countryside was beautiful. Maggie’s second tour of duty was in Iraq, where she was stationed in Baghdad, from May to August of 2007. She was commander of the 9th Forward Surgical team, made up of 20 staff who practiced emergency surgery. She was a part of the “90-day boots on the ground rule,” which states that doctors who land in combat zones are there for 90 days. This was implemented to allow for an easier return to practices back in the US. Prior to her arrival in Iraq, she had already spent three months in further training at Fort McCoy. They worked in Saddam’s private hospital, which had been taken over by US troops and located in the “fortified green zone” near the palace. Their building sustained indirect fire almost every day, (mortars, rockets etc.) and she described it as busy and scary. In Iraq, Maggie saw many injuries, mainly due to specific weapons, particularly IED’s (Improvised Explosive Device) and EFPs (Explosively Formed Penetrator). These weapons cause devastating injuries, and many burn injuries result from them. There has been an active burn surgeon in Baghdad since 2003, because of the injuries caused by these explosives to soldiers. The objective was to get American burn patients airlifted out within 12 hours. To do this, they would scrub and dress wounds prior to the patient’s flights to Germany. If the soldier was very sick, they would stay until they were safe to move. It was physically hard work and it was very hot. Maggie had to be very precise in her work. The first American nurse killed since Vietnam had been sent to this hospital, and Maggie took care of her. She said it was hard to take care of people you know personally. Maggie, and the physicians stationed with her were ordered to wear body armor after they first arrived, whenever they left the building. After the death of the nurse, these orders were resumed. As Maggie’s tenure as commander was ending, she was transferred to the IMA (Individual Mobilization Augmentee) in an active-duty post. This means that if the Army needs a substitute or additional physician, she is on call for the position (burn unit specialist). Maggie now works at Henry Ford Hospital, in downtown Detroit, as the associate Director of the surgical ICU, and the program director of critical care fellowship.

-

Douglas Brinker served in the United States Army as a truck driving during both Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom.

-

Charlie Brown entered the Service shortly after completing high school in Ann Arbor. He was working at the A&P at the time. After his Basic Training, he was sent overseas. It wasn't too long before he was involved in the Battle of the Bulge. There was a great deal of mud that the trucks that he worked with had to get through. Charlie and his group had to cut trees, so that the trucks could avoid it. There were no power saws, so everything was done by hand. At one point, Charlie was asked to drive one of the trucks, because the regular driver was not available. They hit a landmine and the truck was blown up. The two men next to him received shrapnel wounds. Three men in the back were blown out of the truck, and although they were bruised, they survived. Charlie received minor bruises. After taking a pounding from the Germans, his Colonel decided to surrender. The Colonel told the Unit that they had a choice. They could surrender to the Germans or try to find a way to escape. Charlie and a group of about 50 G.I. 's decided to try the latter. The 50 plus group spent a total of 4 days behind the German lines. During this time, the group tried to avoid detection. Charlie reported that one time he was so close to a German soldier who was looking for his buddy, that he could have tripped the German. Of course, he didn't. Another time, the exhausted group took a nap. One of the other soldiers woke Charlie, because they were in the middle of a German tank assembly area. For all 4 days, Charlie only had one candy bar to eat. When the group finally got back to the American lines, they all ate much better, but since they had not eaten for so long, the food did not stay with them. Charlie was still in Belgium when V-E Day was declared. Afterwards, they were packed up and prepared to go to the Pacific. Everyone was relieved when V-J Day was declared. He then started his trip home. While awaiting his discharge, Charlie was in Indiana, near enough to his relatives to visit. On one occasion he was taking a shortcut through a cemetery. There was an empty grave that he jumped into, to see how it felt. His cousin told him to get out. The gravestone was for CHARLE W. BROWN. He used the G.I. Bill to get an Associate’s Degree from Cleary College. He then went to work for the State of Michigan, and finally worked up to Assistant Business Manager at the local State Hospital. Charlie was married for 50 years before his wife died. His second wife was a widow after 40 years of marriage. They have been married for seven years. Charlie said that he has been married for 97 years.

-

Donald Brown volunteered for the draft, after one and a half years at Harvard. He was feeling guilty about being one of the few young men in upstate New York who was not serving. Shortly after entering military service, he was put into the ASTP program, and given a choice of which college he wanted to go to for his studies. He chose Indiana State, where he later met his wife. Eventually, he was assigned to a Medical Unit of the 20th Armored Division and was sent to Europe. After months of minor skirmishes, his unit took part in a major battle outside of Munich, where there were many casualties. On May 1, 1945, his unit was sent to Dachau near Munich, "before it was cleaned up for the Tourists." He never forgot what he saw there. After V-E Day, his unit was meant to be sent to the Pacific. On one of the train trips through France, he was told to go up to one of the front cars. He chose to stay with his unit, which turned out to be a lifesaving choice. The first four cars of the train were completely destroyed in a wreck. While on furlough, just prior to being sent to the Pacific, he got married, and soon afterwards, the Japanese surrendered. Donald spent 13 years teaching at Berkeley after having completed his studies. There, he was eventually fired because he refused to sign a loyalty agreement. He went to Bryn Mawr College, and in 1964, began teaching in the Psychology Department at the University of Michigan, where he retired in 1997. He currently lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and teaches a class on WWII at the University.

-

Bruce Bryan was born on May 20, 1920, in Metro, South Dakota. He always knew he wanted to be a pilot and joined the Air Corps in 1941. His basic training began immediately upon joining the service. At first, Bruce was too underweight to become a pilot, but within a few weeks he gained 14 pounds, making him eligible for pilot training. Three months after he joined the Air Corps, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. For the first three years of the war, Bruce remained in the United States. When he was finally sent overseas, he began flying missions over Italy. One day, his plane took two direct hits and went down. He was quickly captured, and spent the next eight months in a POW camp in northern Germany. Although the Germans allowed him to write letters, his family never received these letters, and were told he was missing in action. Bruce states that for the most part, his treatment was acceptable. One guard did "knock him around" but that was not the treatment that he usually received. In April 1945, Russian troops liberated his camp. When VE Day arrived, he was turned over to U.S. forces. In May 1946, Bruce got married. He and his wife of over 60 years live in Allen Park, Michigan.

-

Joseph Butcko was born in Ypsilanti, and at the time that World War II broke out, he was apprenticed in the tool and die business. He was drafted into the armed forces at age 19. Joseph was already married at that time, to his high school sweetheart. Both of his brothers were also serving in the war, both in the Pacific Theater. He chose to enter the Navy and went to basic training at the Great Lakes institution, in Chicago, IL. Joseph traveled briefly to Norfolk, VA, and then was sent back to Chicago, to practice gunnery at Navy Pier. He was eventually shipped out to Guam, as a helmsman on a Landing Ship Tank (LST). There were over 100 men on his crew, and despite the fact that it was considered a big crew, he eventually got to know every soldier on it. While on Guam, he saw many soldiers returning from the battle of Iwo Jima in ambulances and taken to the hospital up the mountain - this experience really drove the reality of war home to him. Joseph took part in the attack on Okinawa, in which he drove a shuttle landing craft (a small craft) back and forth from larger boats, to carry marines to the beach. There were many Japanese Kamikaze planes involved in this battle, and he saw his brother's ship hit by two Kamikaze planes - luckily, no one was killed. While serving in the Pacific, Joseph ran into many friends from Ypsilanti, as well as both of his brothers. After the war was over, Joseph served in China, keeping the peace. He also helped facilitate the transportation of Japanese soldiers and civilians, who had been occupying much of China, back to Japan. When he was discharged from the Navy, he returned to Ypsilanti to work in the tool and die manufacturing business.

-

Mr. Campbell was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, but was an American citizen moved to the United States when he was young. Wanting to join the conflict, Mr. Campbell crossed the Detroit River to enlist in the Canadian Royal Navy. Even though he was born in Canada and was a Canadian citizen, he was often referred to as a Yankee. The veteran was given a Canadian Naval Ensign that flew over his ship during the Invasion of Normandy. During this oral history, Mr. Campbell describes several experiences he had in the North Atlantic and in the British Isles.

-

When he found out that there was a good chance that he was going to be drafted into the Army, Chuck decided that he would rather enlist in the Navy. He did so in 1941 and went into officer’s training. After his training in Chicago, Illinois, his orders were to report to Charleston, South Carolina on the cargo ship AKA6 U.S.S. Alchiba. While on the Alchiba, he traveled with its cargo to Bora Bora, Chile, New Zealand, and Fiji. Chuck finally ended up part of the invasion of Guadalcanal. After the invasion, his ship made many trips to the island Guadalcanal with cargo. During this time, the Alchiba was torpedoed twice, so after the ship had been repaired, it returned to the states. Chuck then got orders to report to a new ship, the U.S.S. Whitley AKA92, also a cargo ship. While aboard the Whitley, Chuck was at Iwo Jima and Bougainville. The ship headed back to the states due to a cracked stern and was in Hawaii when the war ended. After the war, Chuck remained in the Navy, and went on to the Philippines and Japan. At this time, he became a Lieutenant Commander. After serving in the Navy, he met his wife, and came to Michigan State University, to get a degree in landscape architecture. He went on to get his masters from Harvard, then taught at Cornell for ten years and Michigan for twenty-seven.

-

Bill Carter was born in Huntsville, Alabama on July 15, 1941. His family moved to Detroit when Bill was very young. He did not complete high school, but later got his GED. His father helped to get him into GM at the age of 18. Although he tried to join the Army, they refused him, but drafted him later at the age of 23. With only a few months remaining on his tour, he was extended for six months and sent to Vietnam, where he was a cook for the "Grunts." After leaving the Army, he returned to GM and was able to retire at the age of 47, after 30 years of service (Army time counted towards retirement). Bill never married; but he did have a couple of long-term girlfriends, although he has no children. He receives medical care at the Veterans Hospital in Ann Arbor. Although he had malaria when he was in Vietnam, it has not returned. He is still being evaluated for the effects of "Agent Orange" since he does have breathing problems. Bill now lives in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

-

Mr. Chase was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan on February 17, 1922. He graduated from St. Thomas High School in Ann Arbor in 1941. He was drafted into the Army in November 1942, serving in the 409th Infantry, 103rd Division. Mr. Chase was deployed to the European Theater, arriving in Marseille, France. Mr. Chase saw action on many occasions and was ordered to the front line by his commanding officer. As they traveled north from France, they either slept on the ground or in foxholes. Winter time was difficult due to the cold weather. On occasion, they were able to stay in the homes of civilians. Since they could not speak their language, most communications were through hand jesters and smiles. Many of the homes were occupied by women and children only, as the men were off to the war. He was an anti-tank gunner who received the Bronze Star, the Combat Medal, a Good Conduct Medal, Infantry Badge, Victory Medal, American Campaign Medal, and the European AFR Mideast Medal. After his service in France, he moved on to Germany and Austria. Mr. Chase was honorably discharged as a PFC, in November 1945. Post service, Mr. Chase worked for 43 years at Michigan Bell, as a Local Testing Technician. He was also President of the local union chapter of the Communication Workers of America for 25 years, and a member of the Ann Arbor Chapter of the VFW. Mr. Chase was married (widowed) and had four children, seven grandchildren, and five great grandchildren.

-

Mike Chirio enlisted in the army upon completion of his degree at the University of Michigan in history, and a minor in international relations. He was also an ROTC member, and is able to speak several languages. Mike entered the army on October 11, 1953 and was sent to Fort Benning in Georgia for officer training. He then moved on to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for basic training, where he became company commander, because he was the only officer in the company. Mike stayed there for nine months. At Ft. Benning, he was part of an experimental program (Operation Gyroscope), focused on keeping new soldiers together as a unit. Mike then transferred to Fort Richardson in Alaska, where he stayed for two years. He discussed the lack of fresh food during his time there, and the excitement of the wives when his unit was transferred to Ft. Lewis in Washington, where fresh food was available. Mike spent three years in Washington and was part of the 4th Infantry division there. He spent time at Camp Desert Rock outside of Las Vegas, for nuclear testing maneuvers. Here, Mike was promoted to a First Lieutenant, and then Captain, and a rifle company commander. His unit returned to Fort Lewis. He was then appointed to a position at Central Michigan University, as an ROTC instructor. Mike remained there from 1960-64. In 1964, military intelligence became a separate branch, and he was invited into this unit by a Lieutenant General, via a letter. His next stop was in Maryland, but outside of Baltimore, where he went for more training. He had orders to go to Turkey, but they were changed and he was sent to Vietnam instead. He arrived in Vietnam in February, 1965 as a part of the Army Security Agency (the electronic intelligence part of the army.) His unit was the 3rd RRU (radio research unit) of the 509th ASA battalion (Army Security Agency) and they were stationed outside of Saigon (on an airbase). Their job was to monitor communications including radar, voice, etc. and analyze it. They employed linguists, morse code specialists, etc. He was the security officer for the group, and his job was to keep the enemy from gaining information about what the group was doing, as well as to protect the physical security of the staff (150 military MPs assigned to him). At one point, his staff included an MP dog platoon. When Mike returned from his first tour in Vietnam, he went to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. In 1968 he was assigned to Detroit as part of the 13th MI group during the race riots. His job there was to run background investigations, and his rank was now Lieutenant Colonel. In 1971, he was sent on his second tour of Vietnam, as the Chief of Counterintelligence for the US army there. Mike was responsible for all of its counterintelligence, including keeping information from the enemy, and interrogating POWs. He returned home in 1972, and retired from the army in 1977. Mike became a professor of Military Science at Eastern Michigan University. At the time he arrived, cadets refused to wear uniforms because of harassment. He insisted that they wear uniforms, and talked to professors to calm things down. He spent five years in that position, then retired and stayed on at EMU for 24 more years, as the budget officer.

-

While a student at the Lawrence Institute of Technology, John volunteered for aviation cadet training in the fall of 1942. He was called up in February 1943, and reported for basic training in May, at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. In September 1943, John was dispatched to Twenty-Nine Palms, California for his primary flight school and advanced training. In the summer of 1944, he was assigned to 8th Air Force Combat Operations Training, at a base in Tennessee. Once in England, his crew served as a replacement flight crew for the 8th Air Force 100th Bomb Group, commonly known as the “Bloody Hundred.” While overseas, John and his crew flew 32 missions in Germany, including one that ended in a crash landing in Belgium, on January 5, 1945. His crew’s tour of duty ended on March 8, 1945. Upon returning to the United States, John completed his education at the University of Michigan and MIT.

-

Benjamin Clark was born on November 11, 1919, in Fogo, Newfoundland. He enlisted in the Army Air Force following high school. After basic and advanced training, Benjamin was assigned to the 306th Squadron "Hells Angels" as a waist gunner on a B-17. After six missions, his plane was shot down and he became a POW. Of the ten crew members, only seven survived. After his capture by the Germans, he was taken to a Stalag 17-B where he spent more than two years. Since there were spies in the camps, he was especially careful to whom he spoke. After two years in camp, all prisoners were forced to walk 800 miles to the front lines, because the Germans were trying to avoid the Russians. General Patton rescued the prisoners and informed them that "...you guys are back in the U. S. Army." Mr. Clark was discharged on September 27, 1945 and returned to Dearborn, Michigan.

-

Robert Colley was born in Petoskey, Michigan. He was drafted in November 1943, and went to Camp Blanding, just outside Jacksonville, Florida, to do his basic training. After completing basic training, he was granted 2 weeks leave. His next stop was just outside Boston to another camp. From there, Robert was shipped to England to replace troops who had participated in D-Day. He landed 9 days after D-Day, and was assigned to an armored division. While in Normandy, they were fighting in hedge rows, which were hedges used to help hold the soil. The division couldn’t make much headway because of the hedge rows, and it was only after about six weeks of fighting that they finally broke out of the hedgerows and made their way to Paris. Robert helped liberate Paris four months after his unit landed on European soil. He was captured in Aachen, Germany, when his unit was under the command of a new colonel. They fought their way into a valley, and when they got down there, a German tank was pointed down at them. Out of 139 men, 39 were captured, the rest were wounded or killed during the battle. Robert was taken to Camp 7A, and then transferred to Camp 12A. Eventually, he was brought into East Germany, where they were treated fairly well, although they never really got enough to eat. Most of his captors were soldiers who had been wounded on the western front, so now they served as guards. While at the camp, if they worked on a nearby farm, they were given more to eat, as a reward for working, by the farm owner. Robert worked as a harvester on a sugar beet farm at one point. During the winter of that year, he worked on the railroads, pounding stones underneath the ties to level the track. He could tell that the war was getting more intense, and that the Russians were making headway. From their location, POWs could see the supply trains, people, survivors from the Eastern Front increasing in number every day. There were many wounded coming in as well. A few months later, the POWs heard tanks and artillery getting more pronounced. The next morning, the Russians were outside their camp, sitting on their tanks. The POWs were liberated. Robert’s time as a POW had lasted for 8 months. Many Germans fled their farms as a result of the Russian advance, so he and his fellow POWs took a tractor, and headed for the western front. It took about a week to reach the western front. The POWs got to a river and Russian soldiers helped them cross, to get to the American side. There, the former POWs were directed to a camp, to sign in and give their serial number. They were then taken to Belgium and put on a boat back to the States. Afterwards, they were given a 60-day leave. Robert went down to Miami, and spent about a month there, before being sent to New York. He stayed for about three months in a camp, until an order came down to discharge any POWs, and Robert was discharged. He attended the University of Michigan under the GI bill, and graduated in 1949. Robert specialized in physical education, and he went on to become a stock trader in Ann Arbor. He married in 1950 and retired in 2002. He has two daughters.

-

Mr. Collier initially enlisted in the United States Marine Corps in 1944, but the Second World War ended before he would see combat. Interested in officer candidate school, Mr. Collier would be accepted into the United States Army and into West Point in 1948. Serving three tours of duty in Vietnam, Collier served with both Army Special Forces and the 1st Cavalry Division. After his retirement in 1972, Mr. Collier completed his graduate studies in history, and would teach history at Eastern Michigan University and the University of Michigan for many years.

-

Martha Cothorn was born in a small coal mining town in West Virginia (Besoco). When the mines closed, her family moved to the Detroit area. Her father took a job as a crane operator for Jones and Lockland. After attending grammar and high school in Highland Park, she undertook her nursing training at Hillard, in New Orleans. Martha joined the Army Reserves and received her final two years through the Government, in exchange for three years of active service. Martha's basic training took place at Fort Sam Houston, in Texas. Within nine months of entering active service, she was assigned to the 67th Evacuation Hospital, in Qui Nhon, Vietnam. Eventually, she became Head Nurse in the Medical and Psychiatric Units. The Evacuation Hospital would receive patients directly from the field and attempt to patch them up. Patients would either be returned to their unit or transferred to the Field Hospital in Saigon. Typical patients had hepatitis, malaria, or PTSD. Suicides were not unusual. Martha met her husband in Vietnam. She was eventually transferred to Fort Devens, where she got married. She went into the Reserves after her marriage because her husband, who was in the Diplomatic Service, was assigned to Laos. Southern Cal University had a branch in Seoul, and she was able to get her master’s degree from that unit. Martha spent 30 years in active and reserve service. When she returned to civilian life, she worked at the VA Hospitals in Detroit and Ann Arbor. She has two adult children, both of whom graduated from college and live in other towns. Martha joined the Vietnam Veterans of America when she was in Washington. When she settled in Ann Arbor, she joined the local unit of VVA Post 310, and is currently the president, the first female president of it. Martha has many awards, including the highest non-combat medal, and the Bronze Star. She currently lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

-

Claude Curry was born on February 1, 1921. Before the war, he worked on sailboats. When he was twenty, he knew that he was going to be drafted. He did not have a college education. Therefore, he did not receive high enough math scores to get into the Air Corps. He was sent to the 24th Infantry Division. Before leaving the country, Claude was threatened in a racist manner and hit the man responsible. He was sent to Honolulu, Hawaii for infantry training. From there, his division was sent to Saipan. On the first night there, he was sent with other men to set up an ambush. In the middle of the night, another soldier in a separate squad made a noise by mistake. Claude and his fellow soldiers were unable to assist and had to wait until morning to observe the scene. None of the three men could be found, only their dog tags. The next day, Claude was sent out to the foot of a mountain near the ambush site, in order to clear out some caves the enemy was hiding in. During the fight, another soldier stood on Claude's back and shot a flamethrower into the nearby cave. A day or two later, he was ordered to check for bodies. He was relieved of duty due to the traumatizing experience. From Saipan, Claude was ordered to Okinawa for two or three days, during the height of the fighting. After Okinawa, he and 126 other men were sent to an unidentified island nearby. He stayed there for six months. Meanwhile, some of the enemies were located on an adjoining island. Before Claude was ordered to engage the enemy, the war was declared over. During celebrations, a couple of soldiers fired rockets that hit a small cargo ship. A typhoon soon hit the island. Despite orders not to move, Claude went in search of shelter. He went out into the storm and made two miles' progress in four hours, with floodwaters coming up to his waste. After braving the storm, Claude was sent back to Okinawa from November 1945 to April 1946. He was discharged in May of that year, and became a bus driver until he retired at the age of 55.

-

Robert had just finished his second semester at U of M when he was drafted. He was living in Ann Arbor, but he was drafted from Vermont because his parents lived there. On June 22, 1943, a got on the train in VT and traveled to Fort Devens. Robert was very nervous because he had entered a completely new environment and wondered what was in store for him. He was sent to infantry basic training in South Carolina in July 1943 and was there for 13 weeks of training. After completing training, he was selected for the Army Specialized Training Program, which gave additional technical training to soldiers. Robert was sent to the University of Connecticut and enrolled in the basic engineering curriculum. He thought it was a poor choice because he was a liberal arts person, and he wasn’t sure that he would succeed. After six months, the program was scrapped anyway, and Robert was sent to the 78th Infantry Division in Virginia, in the spring of 1944. While in Virginia, he prepared to be sent to Germany. He was assigned to a heavy weapons company and was asked by the Motor Sergeant to drive a jeep for the squad. Robert said yes (it would get him out of all the marching!), and he was very glad that he was selected for this position. In September 1944, he was sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey where he boarded a troop ship. Robert landed in England about 10 days later (just a few months after D-Day). He was in England for a few months, getting equipment together, and by late November he crossed the channel, and landed in France. From France, he headed to Belgium and Germany. On Dec 13, 1944 he experienced his first day of combat. His 78th division was replacing another infantry division that had been in combat since D-Day, and the 78th division was just over the German border in Simmerath, a small farming community, when they experienced fierce fighting. He was not on the front lines. His job was to carry a trailer (behind his jeep) with a machine gun mounted on it. On the first day, he was ordered to carry ammunition up to a front-line post. As he was carrying them, a mortar landed nearby, and he caught a small bit of shrapnel in his arm and leg. When Robert arrived at the post, the aid man noticed that he had blood on his arm. Robert was told to go to the aid station to record the wound, receive treatment, and receive a purple heart. The doctors could not find the shrapnel in his arm, so he was sent to Paris for more treatment. He was away from the front for about 45 days. By the time he got back to his company in Germany, many of his comrades had been killed, captured, and wounded. Most of the company was made up of new people, strangers to him. His company had held the northern flank of the Battle of the Bulge, and he resumed his job as a jeep driver. In early March, his company moved south; they were the second infantry division to cross the Rhine River. They entered the Ruhr Valley in early April, within a few weeks of victory in Europe. Robert never fired a weapon in combat, since he was a driver. He thinks he was very fortunate to have fared so well, since he did not have to be at the front. Just after Victory in Europe day, his division came across a Prison camp (not a concentration camp, but a prison labor camp), and they liberated it. After the war ended, they ended up in a holding area, in central Germany and thought that they would be sent to the Pacific Theatre. Instead, his division was picked for occupation duty in Berlin. From October 1945 to March 1946, he was on occupation duty in Berlin with his division. Robert became a clerk for a few months, which he liked better than driving a jeep. In March 1946, he was discharged and sent home. He returned to VT, but his father had died while he was away. Robert worked that summer in Vermont, and then went back to Ann Arbor in September 1946, to finish at U of M with a degree in Psychology.

-

Mr. Davison was drafted into the United States Army in March of 1943. Mr. Davison was known as a "Point Man" within the Army, it was his responsibility to be at the front or "point" of any engagement. At one point during his service in Western Europe, Mr. Davison was shot in the arm and captured by German forces. Considered a prisoner of war and injured, Davison was taken to the Stalag 2-B installation. Mr. Davison recalls in this interview the horrific conditions in which he lived for five months in German custody, and how he believed himself to have no hope. He and many of the other POW's he was with, describe how grateful they were for being liberated by American forces.

-

Herman Deal was born in rural Georgia, in 1923. After completing high school, he took a job building ships. After a year, Herman and his buddies enlisted in the Air Corps, because they were promised that they would be together there. That lasted only a few weeks before they were separated in different training programs. His training took him to Boston, Texas, and the Willow Run plant in Michigan where the B-24s were built. This is where he met his future wife, Helen. Herman learned everything there was to learn about the B-24, including how to pilot the plane. He became the third (emergency) pilot of one. Herman's plane was shot down by very heavy flak on his first mission, to attack a submarine base at Toulon. After he was captured, Herman occupied himself with useful activities, including attending classes, for which he eventually received 18 college credits. Herman's camp was in Austria, but when the Russians began getting close, the entire camp population marched through Germany to Lenz, in the so-called 600-mile death march. His group was finally liberated by the 3rd Armored Division, in Patton's group. After returning to civilian life, Herman became involved in several successful businesses. Today, he and his wife of more than sixty years live in Ann Arbor. Although he is "retired," he works every day. Herman has been honored as one of 21 successful business people in Ann Arbor.

-

Kenneth was born in Dearborn, Michigan, on July 11, 1945, and grew up in Lincoln Park, Michigan. After finishing high school, he worked in a supermarket. Kenneth was drafted in 1965, and after basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky and advanced training at Fort Lewis, Washington, Kenneth was shipped to Vietnam. His division went as a unit. The trip took 29 days, and at times the weather was very rough, with there even being a typhoon. The division's first location was Tuy Hoa, where they spent four months. They were then sent to Pleiku, near the Cambodian border. Kenneth described having experienced heavy fighting in both locations. He received his first Purple Heart on May 1, 1967 because of shrapnel, and his second exactly one month later. "Friendly Fire" caused deafness when an artillery shell exploded near his location. Although Kenneth served near and next to soldiers who were exposed to Agent Orange, he has been found to have not had any symptoms to this day. Kenneth returned to his supermarket job after his military service, but he eventually went to school to study accounting. His specialty was payroll, and he ended up working for several different companies. Because of his multiple injuries, he retired in 2001. Since his retirement, Kenneth has been a volunteer at local schools. He was married for 39 years, divorcing in 2010. Kenneth talked a great deal about his "blood brother," with whom he pledged to "trade" blood if or when needed. His unit has a reunion every two years. This year, the reunion will be in Tennessee, and in 2012 the reunion will be in Washington, D.C. He is looking forward to visiting Washington, D.C., since he has never had the opportunity to visit the various military memorials there.

-

Joseph is from Michigan and was in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), in the Upper Peninsula. He was drafted in August 1943, but the army let him finish high school before he entered the service. Joseph was sent to Fort Benning for training when he was around 20 years old. He had only 13 weeks of training before going to school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and was there for several weeks of engineering training. Joseph failed on purpose, so that he would be able to join the army immediately, rather than after college training. He joined the 104th Howling Timberwolves at Camp Carson, in Colorado, for training until they went overseas. They trained at night and were known as “Night-Fighters.” Joseph only fought in one daylight battle while overseas. He landed in Normandy 3 months after D-Day (D-Day+90). The 104th moved through France and into Belgium. Three days later, they received orders to get ready to fight in Holland, where they fought to free the port of Antwerp. Next, the 104th crossed into Germany over the Roer/Rur River to Aachen, to assist the 1st division. Joseph was in a mortar battalion, and was a squad leader, although he was never formally recognized as such. Another squad leader didn’t like him and denied knowing him when asked. Joseph’s unit spent 195 days in constant combat with Germans. This combat took place from Holland down to Aachen, and until the war’s end. He only fought 120 of the days, because he was wounded. Shrapnel from a shell hit him, and he lay for eight hours, waiting for rescue. He was put on a train to Paris, and then to England. He woke up in a hospital in Oxford. He stayed there for three months while he recovered. He was finally sent back to the States, and he arrived in southern California, where he was discharged. After his discharge in 1946, he attended Michigan State University, and worked for GM and Chrysler, as a quality control manager. His unit, the 104th, has had a reunion every labor-day weekend since 1946.

-

Timothy Driscoll was born on Staten Island, New York on July 5, 1945. His father was a chef, and the family moved a great deal. This resulted in Tim attending more than 20 schools before graduating from high school. Tim worked three jobs after high school, and was drafted in 1965, entering the service at Fort Lee, New Jersey. The barracks floors were so corroded that they collapsed. Since Tim had worked on floors in civilian life, he told the sergeant that he could fix them. Before long, there were ample supplies available to Tim to reconstruct the floors. Doing this kept him out of parades and exercise sessions. He was transferred to Fort Leonard Wood, where the weather was extremely cold. Here again, Tim's suggestions changed the way that things were done in the field. Instead of coffee breaks, he had suggested hot soup, which helped personnel cope with the weather. Tim completed the obstacle course so quickly that the sergeant sent him through again and again. Everyone expected to go to Vietnam and was prepared. At the very last minute, however, Tim and two others were taken off the truck. He spent the next 100 days driving officers and officials around. Tim’s training had been in radio and truck and jeep maintenance. He was an E-4 Specialist and became assigned to the 3rd Armored Division. He achieved a Marksman Award and a Good Conduct Award while in the service. Tim was eventually sent to Germany. He spent 17 tense months in Germany. He was discharged in 1967 and returned home. His division received a Presidential Citation. After leaving the service, he got married, and was living in New Jersey when the Twin Towers were destroyed. Tim's son and wife worked in and near the Towers. Both could have been killed were it not for pure luck. Tim’s job required him to travel frequently. By mistake, his wife took his car keys, and had to turn around, and return home. Tim's son was working on the 35th floor of the Towers, but at the time that the plane hit, he was in the basement getting supplies. The family moved to Connecticut, but within a few months his wife was laid off. These events convinced Tim and his family to move to Saline, Michigan, where he now lives with his wife. His daughter lives nearby with her two children.

-

Mr. Elbert was drafted into the United States Army in 1944. After completing basic training, Mr. Elbert was sent to join Allied Forces fighting for control of the Italian Peninsula. After reaching Naples, Elbert was wounded by shrapnel fire coming from German soldiers fighting in Italy. He would later be awarded the Purple Heart for his service in Italy.

-

After graduating from Wayne University (now Wayne State University) with both a bachelor's and Master of Arts degrees in Detroit, Michigan, Mr. Eliot enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps. Trained as a bomber pilot for the B-24 bomber, Eliot would be sent to England where he would fly bombing missions into Nazi-occupied Europe. Eliot was shot down by German forces, and would go on to serve 18 months as a POW. At some point the German soldiers of the installation he was assigned to became aware that Mr. Eliot was Jewish and was made to wear a star with the word "Juden" on it. Following his liberation by American forces, Eliot would return to Metro Detroit to serve as the long-time weatherman for WWJ.

-

Fred played instruments early in life, especially in school. He attended McKenzie High School, where he won a scholarship to the Detroit Institute of Technology. One of Fred's first jobs was playing in nightclubs. Early in World War II, Fred worked for Ford Motor Company and was not allowed to enlist because he was a required worker. Then, in August 1942, Fred was drafted and went to Ft. Custer for basic training. He was classified as a musician and posted with the 523rd Air Force Band, which was also known as the 23rd Army Air Force Band. The band was stationed at Camp Shanks, New York, and was on duty to play for the men boarding troop transport ships, bound for Europe and Africa. When his band was shipped out, no one was there to play for them. The ship that Fred was on went first to La Havre, to drop off infantry troops. The band disembarked with them, and then found out they were supposed to go to England. They had to re-board and continue on to Southampton. He spent most of the war playing at hospitals and dances, but very rarely played for big name entertainers. They generally brought their own bands. During his time in England, Fred had the opportunity to travel the country. He discussed the devastation of London and surrounding countryside, the shortages of everything, and the courage of the British people. He was based in Manchester at the Base Air Dept #2, which was an arming stop for incoming planes flown by WACs. He was on base the day of the Freckelton RAF accident, when an RAF pilot lost control of his plane, and it crashed on the base. Fred talked about an unspoken privilege system, which regular soldiers felt that the band members had. Fred's wife, Helen, was his high school sweetheart. She, along with his parents and siblings, wrote to him often. He remembers having to reply to letters by writing in the latrine, for light and quiet. Fred played the saxophone, trumpet, clarinet and flute. He came home from the war in 1945, and married Helen. Fred took a job teaching music at Dearborn's Salina Jr. High School, starting in 1950-51. He continued to teach there for 32 more years. Fred lost touch with most of his war-time friends but keeps a significant scrapbook of photos taken by others and him.

-

Helen is the wife of veteran John Fidler. She was born on February 9, 1921. While her husband was serving in the Air Force, she and her sister got jobs working on the B-24s, at the Willow Run Bomber Plant. They became riveters, attaching the gas tanks to the insides of the wings. One riveter would put in the rivet with a metal gun, and a riveter on the other side flattened it with a bucking bar. Once, one of the rivets put a hole in Helen’s thumb. They were paid in cash, with many two-dollar bills. Nevertheless, she wanted to work for her country and really enjoyed it. Later, in Norfolk, Virginia, she worked at a PX, and had two German prisoners of war working for her. She said that they worked really hard and were glad to be in the U.S., instead of a POW camp.

-

John Fidler was born in Jay County, Indiana, in 1921. In October 1942, since he was mechanically inclined, he enlisted in the Air Force, so that he could work on airplanes. During World War II, the Air Force sent him to aircraft mechanic school in Lincoln, Nebraska. After six months of training, John was sent to Norfolk, Virginia, where pilots were learning to fly and fight with P-47s. He was made crew chief and became completely responsible for maintenance on one of the P-47s, and airplane he was intimately familiar with, and learned to love. During that time, the training outfit only lost two pilots. He was honorably discharged in 1946, having achieved the rank of Staff Sergeant. Fidler flew on the Pride and Honor Flight in 2009.

-

Ellis Freatman grew up in Plymouth and Ypsilanti, Michigan. He graduated from Ypsilanti High School, and was drafted into the Army, entering the service with his longtime friend L.D. Harman. They separated when L.D. went to the Air Force, and Ellis to the Army. Ellis took his basic training in Maxey, Texas, where he was selected for O.C.S. He received high grades and became a 2nd Lt. at the age of 20. Ellis's assignments included posts in different training units. He was sent to Okinawa and was often used as a replacement officer. Ellis led a platoon, but because of his age and lack of experience, he relied a great deal on his sergeant. Although the island was not fully secured, Ellis did not receive any injuries. He was discharged after serving for over three years, and returned to Ypsilanti, Michigan. Upon receiving his discharge, Ellis entered Eastern Michigan University, where he met his wife, and after receiving his degree, he was accepted to the University of Michigan Law School. After 20 years of a highly successful practice, Ellis retired. His one son is also a successful lawyer.

-

Robert Gould was born in Detroit, Michigan on November 13, 1942. His father was of Polish descent and worked as a share-cropper in upstate New York. Bob's mother was of Ukrainian descent. The farm owner was named Gould, so Bob and his brother became known as the Gould boys. His father changed the family name to Gould. Two weeks after finishing high school, Bob joined the Army, as did one of his friends. At the time, enlistees could join for two years, but draftees had to serve for three. After basic training, Bob was assigned to the First Infantry Division. When given the opportunity, he volunteered for the 101st Airborne Division. His 1st Infantry group was sent to Germany, and Bob was transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia for jump training. He qualified for jump status and was assigned as one of the Medics, which served in the clinics and hospitals. All 101st Division personnel were required to maintain their "Jump Status," which meant that they had to jump periodically. When Bob was discharged, he returned to Detroit, and went to school for six years on the GI Bill.

-

James Green was drafted in October 1943. He applied for pilot training but was turned down and was assigned to a B-29 crew, in the 505 Bomber Group, at Tinian Airfield. Tinian is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands, and is about 5 miles (8km) southwest of its sister island, Saipan. During a mission, when James was a replacement gunner, he was shot down over Tokyo. He did not know the names of the other crew members, and this irritated his captors when he was being interrogated. The prisoners were badly mistreated by the Japanese soldiers during their imprisonment. However, James feels that this made him a stronger person, and he has no animosity toward the Japanese people. After the war, James attended Western Michigan University, and earned a B.A. Degree. Later, he was awarded a master's degree from Central Michigan University. In 2005, when he was being interviewed, he indicated that he has 6 children, all boys He also has 13 grandchildren, and his wife was still teaching.

-

Dave Hammond served in the United States Marine Corps during the Vietnam War.

-

Donald Hanson enlisted in the Navy in 1942. He was commissioned as an Ensign in November 1943. He spent WWII as a training officer. His training tasks included Flight Instruction, Jet Training, Gunnery Training, Photo Training, and Nuclear Weapons Employment. After the war, Donald completed his studies at the University of Minnesota. Most of his time in active duty was spent in Korea with the F9F Panther Jet. Hanson flew a total of 70 missions, 51 combat and 19 noncombat. After one of his missions, he landed his plane on an Aircraft Carrier and found over 300 holes in the plane from enemy fire. Hanson got his nickname because he liked flying low. During one training flight, he and two trainees flew under telephone wires. Although he was reprimanded, he felt he got off easy. From that time on, the other flyers called him "Hoppy." Hoppy retired in 1964 as a Navy Commander. He and his wife now live in Novi, Michigan, at Fox Run Residents. Both he and his wife have been very active in a variety of volunteer activities.

-

Mr. Harwell enlisted in the United States Marine Corps in 1942, as he was confident he would be drafted regardless. Initially serving as a military journalist in Washington, D.C., he was sent to the Pacific Theater to report on the Japanese surrender. In 1945, he also traveled to China to report on Japanese war crime allegations in that country. After returning to the United States and his discharge from the Marine Corps, Harwell would go on to broadcast games for the Detroit Tigers for over forty years. Known as the "Voice of the Tigers" Harwell is still honored today by the Detroit Tigers at Comerica Park in Detroit.

-

Phillip Hayner was born in Ypsilanti, Michigan. He joined the Navy directly after Pearl Harbor. Although he was mildly colorblind, Phillip was assigned to the Signal Corps. Somehow, he missed the eye exam at Boot Camp. After Boot Camp at Great Lakes Naval Station, he was assigned to the Signal Corps, and briefly to Navy Choir Company 385. From the Great Lakes, he was transferred to Norfolk, where he was assigned to the Aquitania, which eventually landed in Glasgow, Scotland. On the third wave at Normandy, Phillip was aboard the LCVP, which carried 15 men. His unit was responsible for setting up a Command Post. Most of the action was north of his position. There were times when the German planes unloaded their leftover bombs on his unit. After more than three months on Normandy, his unit returned to England and was assigned to the Empress of Australia, which carried 2,000 German POWs to New York. From there, Phillip’s unit was sent to Camp Pendleton, California where they trained in landing their craft. Afterwards, they were sent to Hawaii, and then on to Okinawa. On Okinawa, their unit was responsible for taking fresh troops to the island, and returning troops to the Philippines, for R & R. Phillip married while he was on leave. Upon his discharge, he and his wife returned to Michigan. They had three children, all of whom did well in their chosen fields. Phillip is a retired tool and die maker, and now lives in Manchester, Michigan.

-

Lester Heddle was born in Milford, Michigan, on February 23, 1918. After completing high school, he was drafted on March 26, 1942. Following training in Texas, he was sent to the South Pacific. Lester spent much of his time in New Guinea, and then Mindoro in the Philippines. He was part of the 58th Air Service Group. Lester did some boxing while he was in the Service. Although he did not receive any wounds, his unit was subjected to Kamikaze attacks. Lester was discharged shortly after the Japanese surrender. He returned home to Michigan, where he received his teaching degree. Lester attended Eastern Michigan University with his wife. Since they had two small children, Lester took classes in the afternoon, and his wife took morning classes. Lester taught 6th grade in area schools.

-

While attending Eastern Michigan University, Mr. Henderson completed his basic training requirements and upon graduation was commissioned in the United States Marine Corps as a 2nd Lieutenant. Mr. Henderson would then go on to serve for several years in Vietnam. After his discharge from the Marine Corps, Mr. Henderson worked as both a pilot for General Motors and was transferred to the United States Air Force Reserve stationed at Selfridge Air National Guard Base in Macomb County, Michigan. Upon his retirement from the Air Force Reserve, Mr. Henderson had been awarded the rank of Major General.

-

Mr. Hill attended Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island, and was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the United States Navy. Being trained as a naval scuba diver and in explosives, Mr. Hill was assigned to a naval base with nuclear facilities in Newfoundland, Canada. Considered an active duty assignment, Mr. Hill would go on to serve in Iceland, and later as an evaluator of officer candidates in Washington, D.C. Mr. Hill is quoted in the interview as being a big fan of the Navy football team. He would serve in his evaluation of officer candidates until 1968.

-

Oscar Hong enlisted in the Army in 1943, at the age of 19. A friend told him that the Army was looking for interpreters, while Oscar was in New York City. He was sent to Miami for his basic training, and then to Springfield, Illinois, for his Signal Corp training. From there he went to Greely, Colorado and eventually to Burma. Oscar's job was to be an interpreter, primarily for the American Services, in the Flying Tigers group. Although he did not fly on any missions, he described the many bombing raids by the Japanese. He said it was boring in between the raids. After the end of the War, he was discharged. Oscar and his family built a very successful restaurant business in the Detroit area. After his wife died, he sold the business and retired. He eventually moved into his daughter's home, but is now living in a retirement complex, in Ann Arbor. Oscar's decorations include a Good Conduct Medal and a China/Burma/India Theater Medal.

-

George S. Hunt was drafted into the Air Force. George entered the service at a time when the United States was very short on flying personnel. After an accelerated training program, George was sent to England. George and his crew flew several difficult missions. One involved a crash landing in England. When George was finally shot down, his plane was shot up so badly that the crew jumped out. George was captured and taken to a stalag, where he spent 14 months. Upon his discharge, George entered college and received his PhD from the University of Michigan in Wildlife. George became a Professor of Natural Resources and taught about birds, trees, and nature until his death in 1971. His history and experiences were relayed by his widow, Virginia Hunt. Although he lived only until the age of 51, he touched many lives and carried a message of being careful of our environment, and of making our land better for future generations.

-

Ed Huse enlisted in the Navy Air Corps at the age of 22, after his third year in college. He took his basic training in California, and his pilot training in Arizona. He took to flying immediately, and commented "I did it very well!" As soon as he learned to land on aircraft carriers, he was assigned to the Monterey. He saw action in Saipan, Tinian, and the Philippines, flying a Grumman Hellcat. Ed described a situation in which he could not get both landing gears down. Therefore, he was directed to land on an island. When he got there, he still could not release his gear, and landed with some difficulty. Although Ed did not receive any individual medals, he did receive a number of Battle Stars. After being discharged, he went into advertising and promotion, at which he felt he would be good, and he was. Ed completed his BA in eight years, going to Wayne State University part time. He had three children, losing his son, who was also a Navy man. Ed was even mugged and had $1,500 stolen. Ed divorced his first wife after 28 years. He now lives with his second wife at Gilbert Residence, in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

-

Robert was inducted on February 8, 1944, after completing one year at the University of Michigan School of Engineering. He had been deferred once, but turned down a second deferment, because he wanted to be part of the war effort. Robert started out in the ASTP program which made him happy, because he thought that he could continue his education. After two weeks, he was headed for basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, and was assigned to the 95th Infantry Division. The 95th was used as a replacement pool for other Divisions that had experienced large numbers of casualties. On August 9, 1944 Robert embarked for Liverpool on an unescorted ship, the USS West Point. Fortunately, the ship was too fast for the U-Boats. After three weeks in England, the 95th was sent to Omaha Beach, where it joined the 3rd Army under General George Patton. Robert’s outfit captured the major city of Metz, taking major casualties. He was then transferred to the 9th Army for the drive on the Rhine River. Although the worst fighting was over, "mopping up" operations took many lives. Robert returned to the United States for a thirty-day furlough, prior to being sent to amphibious training, for the planned invasion of Japan "Operation Coronet." The planned invasion was cancelled after the Japanese surrender. Of the original 44 men in his platoon, he was one of six who came through uninjured. Robert experienced the fear of combat, and he wondered if he would make it to see his parents again. Although not wounded, he did spend 27 months in hospitals because of service-connected TB. With service time, hospitalizations, and reduced workloads, it took Robert ten years to finish college. The 95th has had reunions since 1950, being deactivated right after the War, with diminishing numbers. Last year alone 99 members died. The morality of using the "bomb" stirred up much controversy, but Robert firmly believes that without it, he wouldn't be here today.

-

After the United States entered World War II, Paul Jankoviak received deferments from the draft, because he held an essential job. He felt guilty about this and forced the Draft Board to take him. Soon after he entered military service, he volunteered for the paratroopers, and was shipped to Europe. Paul's Unit jumped into battle during Operation Market Garden from 500 feet. More than 500 planes participated, and Paul witnessed gliders crashing with men still inside them. After 85 days of continuous battles, his unit was transferred to the Battle of the Bulge. They were warned that the Germans were not taking prisoners, but Paul was captured. He was put on a truck that had American markings. German planes shot up the truck even though the people inside were being transported as prisoners. Paul received frequent beatings from the Germans. When he was finally released, the doctor told him he was one or two days from dying. He spent 6 months in hospitals. After his discharge, Paul took a job as a tool and die Maker. He is proudest of the fact that he built his own house and didn't borrow any money for it. Now retired, Paul lives in Lansing, Michigan. He has 6 children and 13 grandchildren.

-

After earning a Bachelor of Science degree from Clark College in Atlanta, Georgia, and completing several courses of graduate work in Chemistry at Howard University, in Washington, D.C., Mr. Jefferson graduated from pilot training school at Tuskegee Army Airfield in January 1944. Piloting a P-51 fighter plane with the distinctive red tail of the Tuskegee Airmen, Mr. Jefferson was shot down by German forces in August of 1944. Jefferson was a POW at several German installations until his liberation in April of 1945. After his discharge from the Army Air Corps in 1947, Mr. Jefferson would work as science teacher and later assistant principal in the city of Detroit. Due to his service as a Tuskegee Airman and his involvement in the community, Mr. Jefferson was awarded a member of the Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame.

-