The Pokagon Wigwam

Following the Exposition’s closure on October 31, several of its attractions found their way to Michigan. The mammoth Garland Stove displayed in Chicago by the Michigan Stove Company returned to Detroit, where it was displayed until its destruction by fire in 2011. The Exposition flagpole and great organ were purchased by the University of Michigan, and they are still in use today. Much of the Michigan Public Schools exhibit was transferred to the State library and installed in one of the alcoves of the State Capitol; the ultimate fate of those exhibit elements is unknown. And one significant exhibit was purchased by the Michigan State Normal College, where it became a campus landmark. A wigwam reportedly built by Simon Pokagon, chief of the Pokagon band of Potawatomi Indians, and exhibited by him at the Exposition, was displayed at the Normal College from 1911 to 1919.

Following the Exposition’s closure on October 31, several of its attractions found their way to Michigan. The mammoth Garland Stove displayed in Chicago by the Michigan Stove Company returned to Detroit, where it was displayed until its destruction by fire in 2011. The Exposition flagpole and great organ were purchased by the University of Michigan, and they are still in use today. Much of the Michigan Public Schools exhibit was transferred to the State library and installed in one of the alcoves of the State Capitol; the ultimate fate of those exhibit elements is unknown. And one significant exhibit was purchased by the Michigan State Normal College, where it became a campus landmark. A wigwam reportedly built by Simon Pokagon, chief of the Pokagon band of Potawatomi Indians, and exhibited by him at the Exposition, was displayed at the Normal College from 1911 to 1919.

Following the Columbian Exposition, Pokagon’s wigwam was transported to his home in Hartford, Michigan where it remained on display in his yard until his passing in 1899. Simon left the wigwam to his close friend and advisor, C.H. Engle. When Engle moved the wigwam to his property a few miles away it became somewhat of a tourist attraction, eventually garnering attention from MSNC students. An article titled “GET THE SPIRIT: Get a Tag and Help Buy Pokagon’s Wigwam” in the May 25, 1911 edition of the Normal News outlines an argument for raising funds to bring the wigwam to the school’s campus:

During the recent Arbor Day exercises, there was exhibited a collection of birch bark articles made by the Pottawatomie Indians, the ruling tribe of this region and keepers of the Great Council Fire of the northwest. In obtaining this collection, it was incidentally learned that there was in existence at Hartford, Mich., a birch bark tepee built many years ago by Pokagon, the last of the great line of Potawatomie Chiefs.

This teepee is 24 ft. high, 16ft. in diameter, and is made of a double layer of birch bark. Moreover, it is in splendid condition and it is something which would be of great value in connection with the work of the Natural Science Department and Training School.

This historic relic is for sale and it seems most fitting that it should be owned by some state education institution rather than by private parties. With this idea in view, the class in Advanced Nature Study has undertaken to obtain it for the Michigan State Normal College.

It has been decided to issue suitable tags during the week of May 29, these tags to sell for the small sum of ten cents. It is suggested that the tags be worn during the entire week and then retained as they will constitute the admission to the dedicatory exercises where we hope to hear the granddaughter of Chief Pokagon (in costume) assisted by as many of her tribesmen as can be contained.

The students were successful in both their efforts to raise funds to bring the wigwam to campus, and their goal of having Chief Pokagon’s granddaughter speak at the dedication ceremony (in “costume”). On June 15, 1911, Pokagon’s wigwam was moved for a final time to the MSNC campus in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and Simon’s granddaughter Julia, accompanied by her husband and children in traditional Potawatomi dress, spoke at the dedication ceremony. She began her speech by describing the sacredness of the wigwam in Anishinaabe culture:

I am glad that I am here; indeed that you have granted to a child of the forest an opportunity to address the teachers and students of the greatest institution of Michigan; am glad this college has honored my race by placing on these grounds the wigwam of my fathers. There is nothing more sacred to our people than ‘wigwam.’ It is as dear to our hearts as ‘home’ to the white race. It brings to us all the kindred ties of father, mother, sister, brother, son and daughter. We too can sing with overflowing hearts ‘Wigwam, Sweet Wigwam: there is no place like Wigwam.’

Dedication ceremony for Pokagon's wigwam at the Michigan State Normal School Campus, 1911.

Dedication ceremony for Pokagon's wigwam at the Michigan State Normal School Campus, 1911.

Julia Pokagon, her husband Michael Quigno, and their children stand to the left; in the back row are Professors Sherzer and Strong - Eastern Michigan University Archives Pokagon's wigwam next to Sherzer hall 1916 from the Eastern Michigan University Archives

Pokagon's wigwam next to Sherzer hall 1916 from the Eastern Michigan University Archives

Pokagon’s wigwam was meant to be a permanent memorial on campus, but lack of maintenance and exposure to the elements damaged the structure and prompted MSNC staff to put the structure into storage in 1919. What happened after it was removed from its location in front of Sherzer Hall is unknown, and its location (if it still exists) remains a mystery to this day.

Simon Pokagon

Simon Pokagon

Simon Pokagon was born in 1830 in the southwest of what would soon become Michigan. His father, the patriarch of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, was involved in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago which ceded the majority of the Potawatomi land to the United States government. As a teenager, Simon claimed to have gotten an education at Notre Dame and Oberlin College, but the only institution with records of his attendance was the Twinsburg Institute in Ohio. Simon Pokagon spoke four or five languages and, as noted by John Low, “bore the reputation of being the best educated full-blood Indian of his time.” Simon utilized his Western education to advocate for his people, and took his concerns to the highest office in the nation where he visited with President Abraham Lincoln on two occasions, and once with President Ulysses S. Grant after the Civil War.

By the 1890s, Pokagon was a nationally recognized Indigenous leader, and his interactions with White society revealed the Potawatomi chief’s dualistic and complex nature. Chief Pokagon was invited to be a featured speaker at the 1893 World’s Exposition in Chicago on “Chicago Day,” which celebrated the 60th anniversary of the day the Potawatomis’ land was ceded to the US government. In his speech Pokagon sought to appease the city’s mayor and White parade goers:

I shall cherish as long as I live the cheering words that have been spoken to me here by the ladies, friends of my race; it has strengthened and encouraged me; I have greater faith in the success of the remaining few of my people than ever before. I now realize the hand of the Great Spirit is open in our behalf; already he has thrown his great search light upon the vault of heaven, and Christian men and women are reading there in characters of fire well understood; The red man is your brother, and God is the father of all.

However, a birch-bark booklet that the aging chief published at the Columbian Exposition, The Red Man’s Rebuke, took on a much different tone, showing Pokagon’s much more complicated feelings toward the colonization and forced assimilation of America’s Indigenous populations.

On behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, the wonder of the world.

No; sooner would we hold the high joy-day over the graves of our departed than to celebrate our own funeral, the discovery of America. And while . . . your hearts in admiration rejoice over the beauty and grandeur of this young republic and you say, “behold the wonders wrought by our children in this foreign land,” do not forget that this success has been at the sacrifice of our homes and a once happy race.

The Red Man’s Rebuke (later retitled The Red Man’s Greeting) was published by Pokagon in order to express his concern for the Western dominance over Indigenous cultures, and was printed on birch bark, a material of spiritual significance to the Anishinaabe peoples of the Great Lakes region.

Newspaper writers in the 1910s readily accepted and repeated the claim that Pokagon's wigwam was built and displayed in the American Indian Village on the Midway in Chicago at the fair, but there is no historical evidence to support this claim. However, this claim was consistent with (and expressive of) widely shared memories about Pokagon's participation in the 1893 Fair, his manufacture of birch bark items, and the presence of wigwams at the Fair. The repetition of the World's Fair claim also shows the power of the Fair in popular memory two decades later.

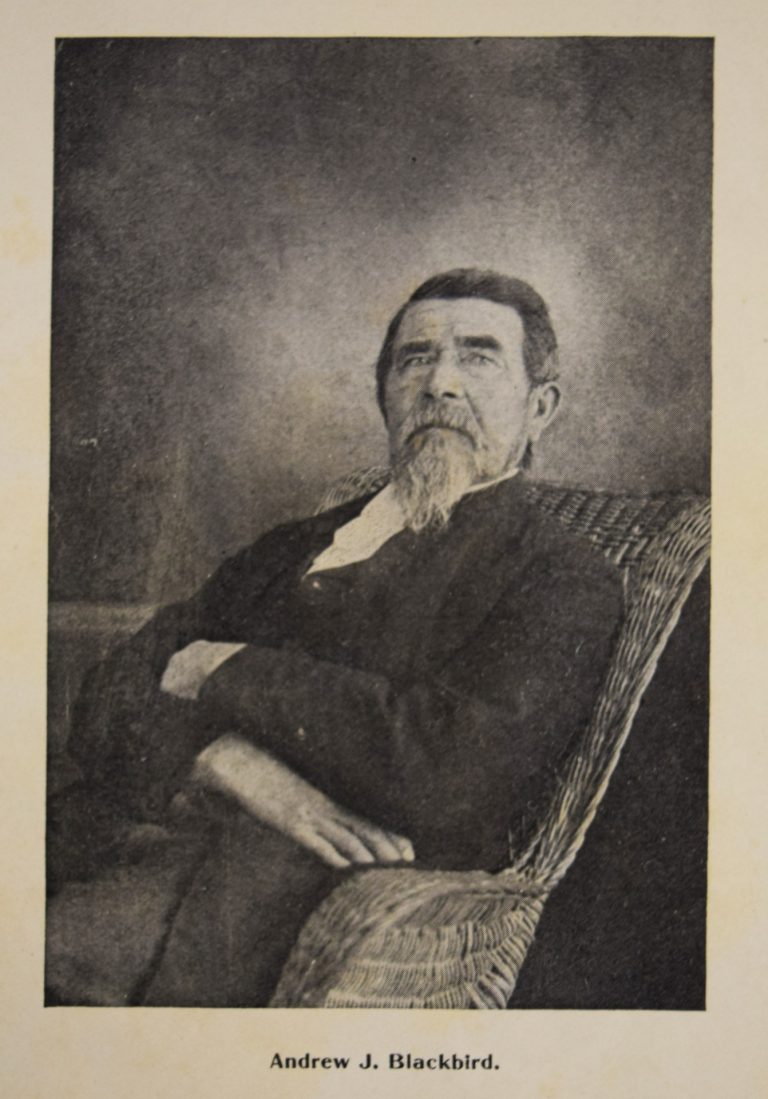

Andrew Jackson Blackbird

While not a participant in the 1893 Columbian Exposition, Andrew Jackson Blackbird, the last hereditary chief of the L’Arbre Croche Band of Ottawa Indians, had close connections to both Simon Pokagon and the Michigan State Normal School. Blackbird was born around 1820 in the grand village of the Ottawa tribe, L’Arbre Croche (or Waganagisi), which is known today as Harbor Springs, Michigan. He was the youngest of Chief Mackadepenessy’s (Blackhawk) 11 children. Blackbird received a few years of Western education at mission schools as a child, but was pulled out of school following the suspicious death of his older brother William, who died in Rome just days before he was meant to be ordained. William’s death led Chief Mackadepennessy to distrust Western education, and led Blackbird to move to Green Bay, Wisconsin to live with his sister.

After working a series of odd jobs for several years, the longest being a five year position as a blacksmith’s apprentice on Mackinac Island, Blackbird traveled to Ohio to continue his education in spite of his father’s wishes. From 1845 to 1849 Blackbird attended the Twinsburg Institute, where he began a lifelong friendship with fellow student Simon Pokagon. After receiving a message that his father had taken ill, Blackbird returned to L’Arbre Croche to care for the ailing chief. The L’Arbre Croche that Blackbird returned to was not the same village he had grown up in. The 1836 Treaty of Washington had ceded the remaining Ottawa and Ojibwe lands to the US government, and while 50,000 acres of land around L’Arbre Croche had been reserved for the Ottawa, many left between 1839-1840 out of fear that the US government would still force them to leave anyway. In order to help protect the land rights of his people, Blackbird helped to negotiate the 1855 Treaty of Detroit. This treaty allotted 40-acre plots to individuals and 80-acre plots of land to families belonging to the Ottawa or Chippewa (Ojibwe) nations who had remained on their ancestral land. In exchange for these allotments, the Ottawa and Ojibwe agreed to dissolve their tribal organizations, severely weakening their tribal sovereignty. As his people struggled to adapt to their new lives under the rule of the U.S. government, Blackbird made plans to receive further education in order to help the Ottawa of L’Arbre Croche acclimate to the Western society that was rapidly encroaching on their land and ways of life.

Blackbird sought to continue his education at the University of Michigan, but Senator Lewis Cass, a leading Democratic politician known as a friend to Michigan’s Indigenous population, thought the Michigan State Normal School would be a better fit for him. Makade-binesi had traveled from Little Traverse Bay to Detroit to speak with Cass about receiving financial assistance from the U.S. government to fund his education and living expenses. After Cass promised to intercede on Blackbird's behalf, he walked from Detroit to Ypsilanti in a blizzard to begin his education at the Normal in 1856, becoming the first student of color to attend the institution. Blackbird had received a letter stating that his tuition, room and board, and clothing expenses would be covered, but unfortunately the Indian agent assigned to provide Blackbird financial aid, Henry Gilbert, disliked him and only provided him with enough funding to cover tuition costs. Blackbird was forced to abandon his education at the MSNS after two-and-a-half years as a result of lacking the necessary funds to provide food and warmth for himself and his new wife Elizabeth (a white English woman he married around 1858). The couple left Ypsilanti in 1860, and returned to L’Arbre Croche. Blackbird occupied a series of political offices upon returning to his home, and, most notably, served as the first postmaster of Harbor Springs, Michigan, managing a post office out of his home from 1869 to 1877.

Although Blackbird was unable to complete his education at MSNS, he utilized what he had learned during the two-and-a-half years he attended to document the language and history of the Ottawa and Chippewa people. In a letter to one of his mentors, Rev. Samuel Bissell, Blackbird stated that the Ottawa and Chippewa grammar book he had written followed the same plans as the Latin and Greek language books used by MSNS instructors. In 1887, Blackbird published the History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, which depicts the cultural practices, traditional beliefs, and history of the two Anishinaabe tribes. Without Blackbird’s publication, there may have never been a historical record of the Ottawa and Ojibwe people told from an Indigenous perspective. In addition to being a published author and Anishinaabe historian, Blackbird also spent his days advocating for his people and fighting for equal rights in a society that viewed him as inferior. The life and legacy of Chief Makade-binesi are honored in perpetuity by the Andrew J. Blackbird Museum, a small institution located in the historic Blackbird family home in Harbor Springs, Michigan.

Andrew J. Blackbird Museum and Historical Marker - Photograph taken by Joel Seewald for the Historical Marker Database

Pokagon's Wigwam and Indigenous Identity

During the eight years Simon Pokagon’s wigwam stood outside the Science Building (today Sherzer Hall), it was a campus landmark. Souvenir postcards depicting the wigwam were made, sold, and sent. When the wigwam was removed for preservation in January 1919, the Normal News asked, “Where is the Wigwam?”, noting that the wigwam had “for many years…held the place of honor in front of the Science building.”

Professor Sherzer’s Advanced Nature Study class had acquired the wigwam ostensibly for scientific and educational purposes. In a 1905 Normal News article on “Nature Study for the Primary Grades,” Sherzer presented the development of human material culture as a major topic in a Nature Study curriculum, and he associated wigwams and “tepees” with the fourth of six stages of human cultural evolution. On June 1, 1911, during the time that Sherzer’s class was busy securing the wigwam, the Normal News ran three articles by Normal students about the birch tree and its importance to Native American cultures.

But the wigwam also served as an occasion for the appropriation of Indigenous identity. On June 14, 1911, the Detroit Free Press reported that at the upcoming dedication ceremony, “A novel feature will be the crowning of one of the students as a princess of the Pottawatomie tribe, who will serve as custodian of the wigwam.” A postcard photo, likely taken on the day of the dedication ceremony, shows Professor Strong and another man standing with a large group of White children dressed in Indian costume. On October 19, 1911, the Normal News reported on a football team victory with the headline, “One Scalp Drying in the Normal Wigwam.”

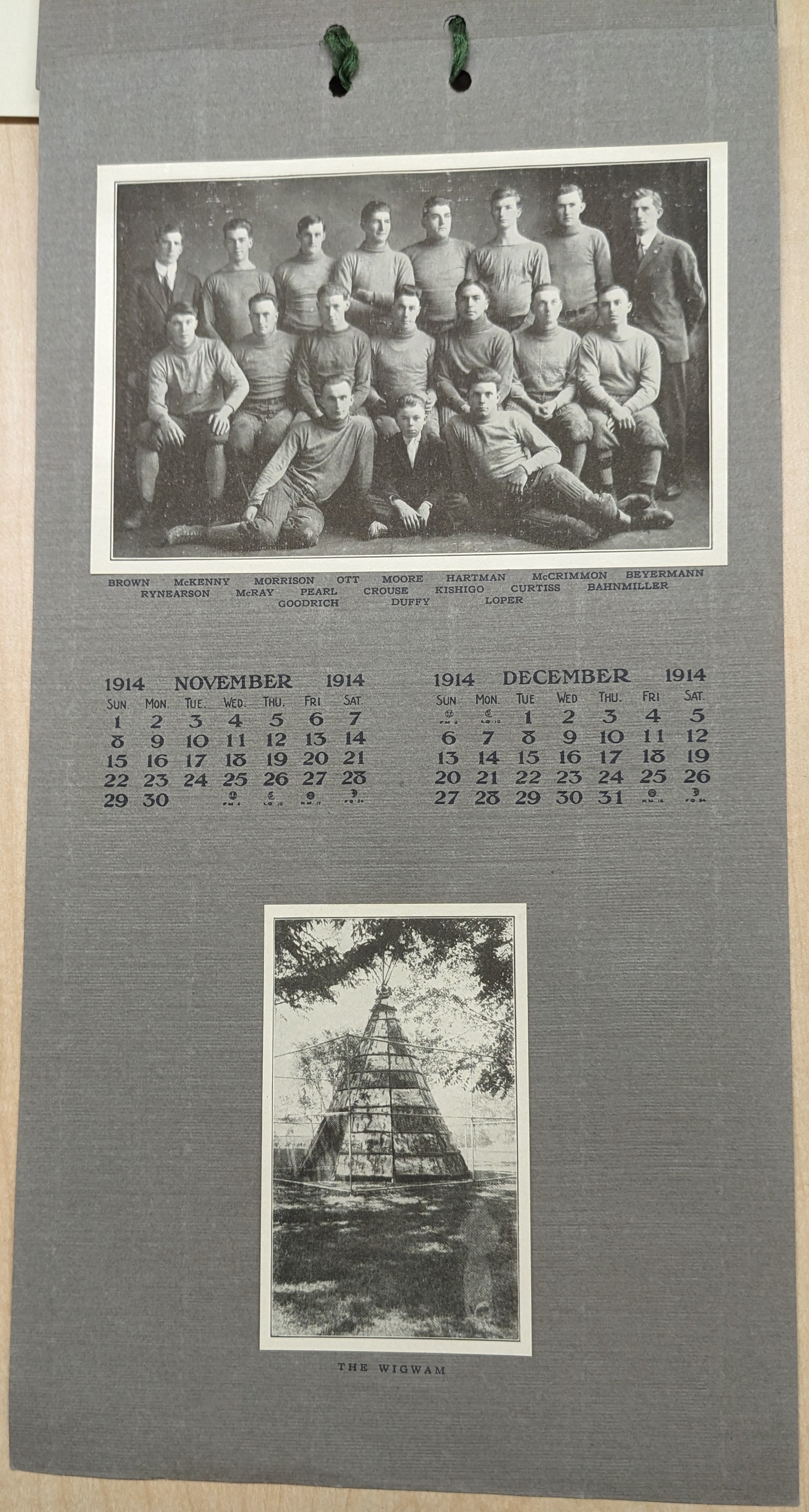

The association of the football team with Native Americans took on added life with the election of William A. Kishigo as team captain for the fall 1914 season. Like Andrew Blackbird, Kishigo belonged to the Odawa community of Harbor Springs. During his two years at the Normal College, Kishigo played football, basketball and baseball, belonged to the Arm of Honor, the leading fraternity on campus, and served as Sergeant-at-Arms for the Class of 1915. Despite his popularity, Normal News reports on Kishigo were infused with stereotypical descriptions. On November 26, 1913, the News reported,

Normal's will probably be the only team in the state next fall with a full-blood Indian at its head, and with the "Chief" to show them how, the boys ought to remove about all the scalps that appear in sight.

A May 22, 1914 article added,

Whether the presence of a vigorous and clever Indian at the head of Normal's squad will strike terror to the hearts of its opponents remains to be seen, but this much may be taken as certain: The "Chief" is not depending exclusively on his ancestral fame to terrorize the enemy.

Kishigo’s captaincy was linked to Pokagon’s wigwam in a 1914 campus calendar, whose entry for November and December paired photos of the team and the wigwam:

Although Pokagon’s wigwam loomed large in the identity of the Normal College in the 1910s, memory of the wigwam faded in subsequent years. After 1919, College publications make almost no mention of the wigwam, and its final fate was not chronicled. Likewise, between Kishigo’s graduation in 1915 and the adoption of the Huron mascot in 1929, Normal News sports coverage rarely associated the Normal’s athletic teams with Native Americans. By recovering this history, we recall how Simon Pokagon’s wigwam embodied the bonds linking both Chicago and the Michigan State Normal College to the Potawatomi, on whose ancestral lands both stand.